Column: Massively Complicated Pomo-ments

Since middle school, I’ve heard whispers of a notorious English class at Archer that is both loved and feared by seniors: Postmodern American Literature, otherwise known as simply “Pomo.” Asking seniors about the class would only prompt them to screech, “Don’t take it!” or to announce with dramatic flair, “It will ruin your life.”

Perhaps I should have heeded their warnings better, as my perspective of myself and my world has been turned upside down by the discussions I’ve had in Pomo. “Nothing makes sense anymore!” is a common wail of despair as students exit class. Knowledge is power, but ignorance truly is bliss.

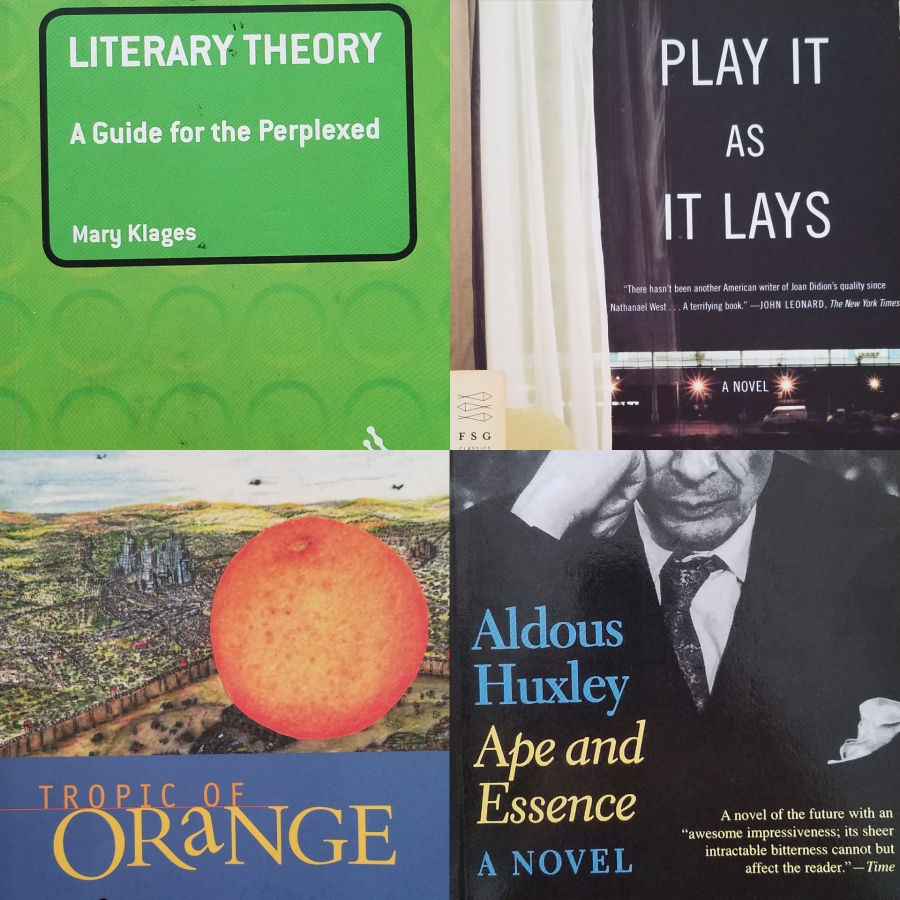

To give a little background, Pomo focuses on how fictional and social realizations of Los Angeles have changed and are changing during the late 20th and early 21st centuries. So far, we’ve read Ape and Essence by Aldous Huxley, Play It As It Lays by Joan Didion, Tropic of Orange by Karen Tei Yamashita, Twilight: Los Angeles, 1992 by Anna Deavere Smith and numerous criticisms and abstracts of literary theory.

I have to attribute a lot of my intellectual development to this class and to thank Mr. Donnel and my classmates, who have encouraged my voice and helped me gain confidence in my speaking and writing on heavy social issues and challenging literary topics.

Once I learned the vocabulary and concepts to articulate my thoughts, I started to think about how I could apply them to my daily life. As silly as it sounds, by viewing the college process as a system, things simultaneously became clearer and more confusing. I saw new methods and ways to understand, to rationalize.

Once, as my mother was driving me from the 803 bus stop at Third Street Elementary in Hancock Park to my apartment in Koreatown, I suddenly remembered something she had told me. Houses in front or behind my apartment are mostly owned by middle-upper class white residents, yet my apartment houses mostly working class Koreans — the majority of them first-generation immigrants.

The racial and socioeconomic divide intrigued and shocked me. How would I go about exploring my curiosity? Where could I best expand my mind and understand my neighborhood and my experiences in a nuanced, compassionate manner?

Writing. More specifically, my Honors essay.

My studies have helped me evaluate my home and school communities, as well as society as a whole, through a variety of critical lenses. At the age of eleven and entering an unfamiliar environment, I would have never imagined myself analyzing the postmodern nature of my neighborhood through social, historical, economic, and political lenses, nor would I have seen myself writing social justice columns for the school newspaper.

Pomo has given me a voice. My voice. Seriously, I talk about being Korean the most in Pomo. And it feels nice to have confidence in my self-expression, to know that my classmates are just as passionate as I am about learning and analyzing the past and the present through a variety of lenses so we can deconstruct societal systems, to love the power of language.

There probably won’t be a class I treasure more than my dear Pomo class.

Audrey Koh became an Oracle columnist in 2016. Her column focuses on popular culture and current social issues through a social justice lens, focusing...

![Freshman Milan Earl and sophomore Lucy Kaplan sit with their grandparents at Archer’s annual Grandparents and Special Friends Day Friday, March 15. The event took place over three 75-minute sessions. “[I hope my grandparents] gain an understanding about what I do, Kaplan said, because I know they ask a lot of questions and can sort of see what I do in school and what the experience is like to be here.](https://archeroracle.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/grandparents-day-option-2-1200x800.jpg)