Column: Food for thought

Photo credit: Norah Adler

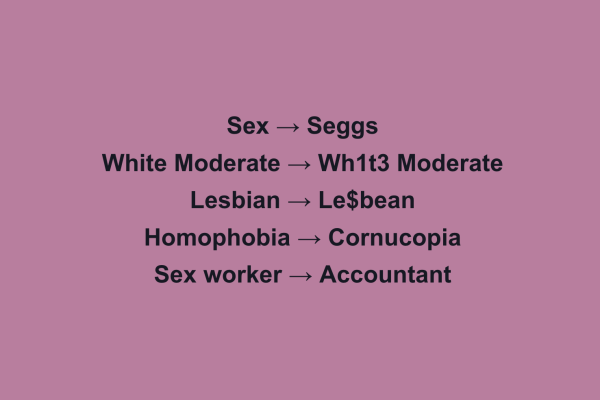

The Archer garden is used by sustainably classes to learn about soil health. One solution to food deserts is local gardens. Community gardens can help build relationships between neighbors, provide healthy foods and improve physical and mental health.

May 20, 2021

When I think of Archer, I think of food: the trick is getting creative. In sixth grade, my go-to student store snack was semi-freezer-burned vanilla ice cream with M&M’s. In ninth grade, buffalo wing pretzel crisps, and most recently, a bowl of honey nut cheerios over a Zoom advisory cereal party.

When I think of my family, I think of food. Especially when we drive an hour out of Los Angeles to eat the best donuts. Sukiyaki, a delicious hot pot of cabbage, beef, shungiku, shirataki noodles and the silence of eating. Many families come together to share a meal and many cultures value food. Subsequently, farming is a sacred part of society.

Food brings security and prosperity to communities, but historically, it has also been used as a tool of colonialism and systemic oppression.

Recently, the term “food deserts” has been popular to point out areas with limited access to affordable nutritious food, impacting low-income communities and often communities of color.

However, in an interview for The Guardian, food rights activist Karen Washington suggests that “food apartheid” is a more appropriate term. “It’s an outsider term,” she explains, “‘Food Desert’ makes us think of an empty, absolutely desolate place. But when we’re talking about these places, there is so much life and vibrancy and potential.”

The New York Law School attributes food apartheid primarily to “race-neutral policies espoused by the government that have had racialized consequences.” With the history of redlining, government policies and financial policies that negatively impact communities of color, race neutral policies today effect a racialized society, and food apartheid is just a result of these policies.

One way in which communities are both tackling racial inequalities and agricultural climate impacts is farming. One farm in Upstate New York is focused on regenerative agriculture and uplifting communities of color, run by Leah Penniman and her family. At her farm, she practices Afro-Indigenous planting techniques to create a self-sustaining farm and support and uplift other Black farmers. In an interview with Penniman, she said that “we need to know [the history of Black people and agriculture and] take pride in that, in this noble Black agrarian tradition and we find that exploring that narrative provides a point of connection, in addition, to obviously the hands-on experience of just being on the land.”

Food has a direct link to community, security, and health, so food apartheids can impact communities, specifically communities of color, mental and physical health. Beyond access to food, white farmers receive more subsidies than their Black counterparts.

Farming is key to defeating global warming. In order to use farming techniques to sequester carbon, we must first address racism and how it intersects with food apartheids.

For individual action steps, keep an eye out for the Justice for Black Farmers Act, a bill to address discrimination against Black farmers by supporting training and access for Black farmers. Other organizations to support are the National Black Food and Justice Alliance, Good Food LA and Archer graduate Sienna Mills’ garden organization Flourish. For more information on regenerative agriculture, listen to the fabulous podcast “How To Save A Planet, Soil: The Dirty Climate Solution.”

![Freshman Milan Earl and sophomore Lucy Kaplan sit with their grandparents at Archer’s annual Grandparents and Special Friends Day Friday, March 15. The event took place over three 75-minute sessions. “[I hope my grandparents] gain an understanding about what I do, Kaplan said, because I know they ask a lot of questions and can sort of see what I do in school and what the experience is like to be here.](https://archeroracle.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/grandparents-day-option-2-1200x800.jpg)