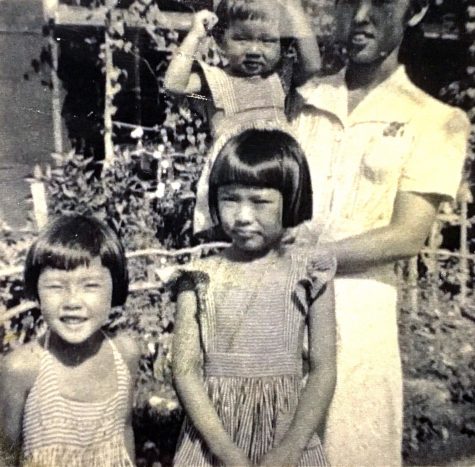

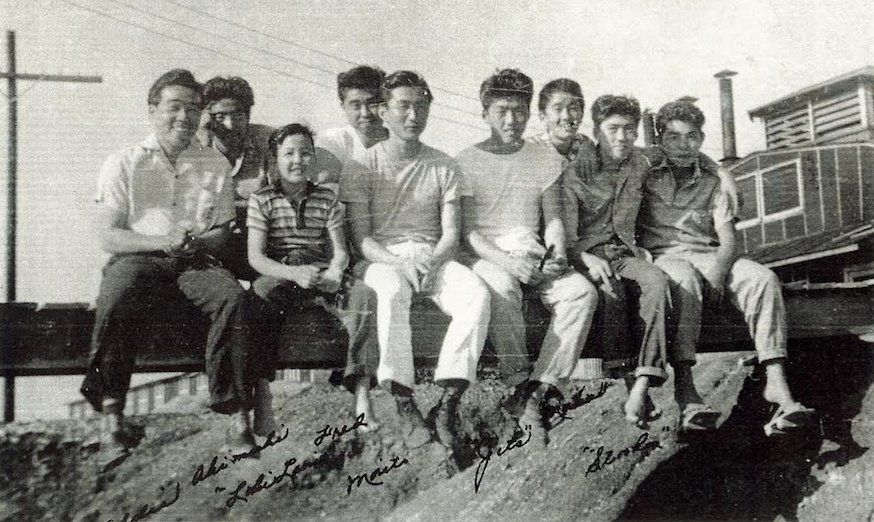

Albert Yoshimura, third from left, spends time with older children in front of barracks at the Rohwer, Arkansas, internment camp. Yoshimura, an American citizen and French teacher Valerie Yoshimura’s father, was a young child when he and his family moved to a camp from their home in Hawaii. Photo courtesy of Valerie Yoshimura.

Lost Years: Remembering the Japanese Internment’s 75th anniversary

April 19, 2017

Feb. 19, 1942, began like any other day, but what Japanese-Americans did not realize was that the day’s occurrences would change the rest of their lives forever.

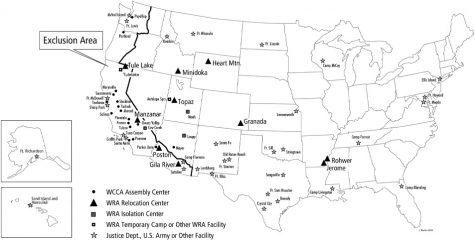

That morning, President Franklin Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066, declaring parts of the United States to be designated military regions “from which any or all persons may be excluded.”

The order subsequently established 10 internment camps across the nation and forcibly relocated Japanese-Americans living on the West Coast and Hawaii as a war precaution.

An earlier Presidential Proclamation set the groundwork for the order and required aliens from Germany, Italy and Japan to register with the US Department of Justice — but only the Executive Order specifically targeted Japanese.

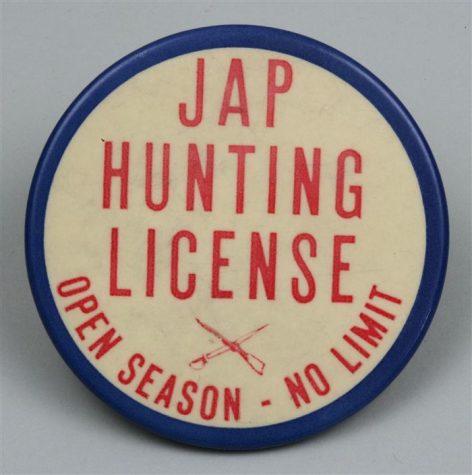

The executive order came just months after Pearl Harbor, which triggered the American entrance into the war in the Pacific. Meanwhile on the home front, suspicions towards resident Japanese rose, and racial tensions flared.

It has been 75 years since the order, but its reverberations are still felt today. Many members of the Archer community have personal connections to the event.

Reporting to Camp

“I learned when I was ten that my dad had been ten when he had been in a so-called camp,” French teacher Valerie Yoshimura said. “I realized it wasn’t the summer camp I had long imagined.”

On Feb. 25, 1942, less than a week after the order, the first large group of Japanese-Americans were ordered to relocate to camps.

Evacuees were given only 48 hours to move, and in the coming days 120,000 residents of Japanese descent were uprooted. Two-thirds were Nisei, first generation Japanese — who were American citizens themselves. Many internees were children and teenagers and had not called any place home besides the United States.

Laura Hakuro Dominguez-Yon’s parents were interned, and she works to record oral histories on internment. Her daughter, Jolina Clement, is the Director of Educational Technology and a computer science teacher at Archer.

“It was difficult,” Dominguez-Yon said. “It was embarrassing and humiliating.”

According to her, leaders in the Japanese-American community were sent away first because they were deemed most suspicious. Those targeted included ministers, language teachers and Japanese American Citizens League [JACL] leaders.

“My grandfather was a truck driver who hauled fish from the pier to the market, but he was also listed as secretary of that fishing company. Because he was listed as an officer, he was suspect,” Yoshimura said. “He was also a language teacher for the Nihonjin Gakko, the language school, teaching Japanese.”

Though initially only Yoshimura’s grandfather Kuniichi was ordered to relocate, his wife and children joined him in order to keep the family together.

“There were only 1,108 [internees from Hawaii], and my family were seven of them,” Yoshimura said. “We didn’t suffer the same level of loss as the people on the West Coast, but it was still an obnoxious abrogation of their rights as American citizens. It was only my grandpa who was the true Issei. Every one of them, including my grandmother, was American born.”

Japanese-Americans were ordered to travel to relocation centers from which they were assigned an internment camp. The largest relocation center was the Santa Anita Racetrack; over 19,000 Japanese-Americans traveled through there and were temporarily were forced to live in horse stalls.

Dominquez-Yon’s family was sent to the Salinas Assembly Center, which was on repurposed rodeo grounds.

“It still had the odor of a racetrack,” she said.

Internees could only bring along what they could carry in one bag, ridding families completely of their assets. They were forced to give up pets, cars, jobs and homes that many had spent their lives working to acquire.

“[Before internment my mother] wanted an education. Typically, farmer’s daughters become farmer’s wives,…but she wanted a profession,” Dominquez-Yon said. “She wanted to become a fashion designer, so she came to LA to go to a Japanese design school and got her bachelor’s [degree].”

However, her career was cut short when the executive order was released. That day, her boss sent her home, and she was unable to continue her career in the same capacity.

Life in Camp

Meri Onishi, an American citizen, was six when she was relocated to the camp in Rohwer, Arkansas, from her home in Los Angeles. Prior to the relocation in Arkansas, was sent to the San Anita Assembly Center and stayed in a horse stall before later being sent to the camp in rural Arkansas by train. She lived in the camp for three years.

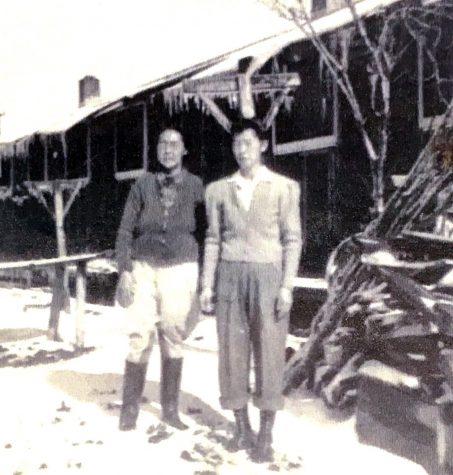

“I remember we had to cover the windows in black material to keep the light from going out. There were barbed wires around the camp, and there were empty towers around the camp so you couldn’t leave,” Onishi said.

The camps were located in desolate, remote regions and internees were not allowed to leave. Some interned compared the conditions to those in the Holocaust concentration camps.

In internment camps, families were forced to live in barracks, which often had no plumbing and little heat.

“Our address was 3-4-F, which meant the third block, third barrack, section F,” Onishi said.

Her family of five shared a single room.

According to National Public Radio (NPR), families ate in communal dining halls, which were notorious for their bad food. Internees ate things like hot dogs, sardines and peaches over rice day after day.

“I remember missing things like bubble gum and popsicles,” Onishi said. “We didn’t have those.”

According to Dominguez-Yon, camps also forced assimilation by prohibiting internees from speaking in Japanese.

Nevertheless, internees strove to create a sense of normality amidst hardship and established schools and governing bodies within the camps. Children played baseball, families grew vegetable gardens and religious services were held.

The camps also brought together Japanese-Americans from different regions who otherwise would not have crossed paths. Dominguez-Yon’s parents met at an assembly center and later married at the Poston, Arizona, camp. While in the camp, they had two children.

“People would say life was easy. They were given three meals a day, had a roof over their heads and didn’t have to work, but still you don’t have the freedom to go where you want,” Onishi said. “You’re behind these barbed wires.”

Enduring Patriotism

Although ostracized from mainstream American society, many Japanese-Americans still felt very American.

“Most of the Japanese felt very patriotic, so some volunteered to join the army [military] to go fight in Europe,” Onishi said.

Service not only allowed for an escape from the camps, but gave the Japanese-Americans that enlisted a chance to prove their loyalty.

Many Nisei fought notably in segregated all Japanese regiments. The most famous of these was the 442nd Regimental Combat Team, which became the most decorated U.S. military unit ever.

“Very few of them have ever been to Japan and most of them cannot speak Japanese. They are as thoroughly loyal as German Americans, Italian Americans, or any other American of foreign ancestry. A category, of course, into which all of us fall,” a 1945 document released by the U.S. Army said of the 442nd, “We must always treat the men just as we would treat any other group of American soldiers.”

Joining the military was a tactic that helped many Nisei, but adversity at home persisted.

Yoshimura’s uncle worked for the military intelligence service during the war. She still struggles with the conflicting messages the internees were sent.

“I just remember being plagued by, ‘What did they teach you? You went to school in camp. How could you say the Pledge of Allegiance? What did they tell you about the constitution?'” she said.

Readjusting

In 1945, internees began to be released gradually after three years in captivity.

“They started a program of early release where internees could resettle elsewhere if they did not go to the West Coast. That’s why there’s big [Japanese-American communities] in Michigan, Chicago, Ohio and New Jersey,” Yoshimura said. “That’s where [my father] met my Irish mother. If internment hadn’t happened I would not have been born.”

The last camp was closed in by March 1946.

Some Japanese-Americans returned to the regions they had previously called home, but without any remaining possessions, there was little incentive to do so. Others sought a fresh start.

Resettlement communities like Gilroy Yamato Hot Springs served as homes for internees as they transitioned back into civilian life.

Dominguez-Yon grew up at the hot springs and volunteers there today documenting oral histories of internment.

“We’re told that 60 families settled there — about 160 individuals,” she said. “Of those I’ve identified a very small handful.”

Even after their release, a lasting stigma around internment remains.

“The number one rule was always: don’t bring shame upon your family. There was an association in the Japanese-American consciousness that talking about internment would remind everyone of the shame involved. Even though they weren’t guilty they felt that,” Yoshimura said. “No one talked about it except in euphemism until the late ’70s early ’80s.”

Shikata ga nai, meaning it cannot be helped, became a mantra of sorts for internees. Many felt helpless and would rather have endured discrimination than cause controversy.

“[My parents] never really talked about it. For them it was traumatic,” Onishi said. “You weren’t given time to think about what you were going to do, they just told you to go here, then there.”

Although Dominguez-Yon was born after the internment, she experienced much of the same.

“My parents told us not to stick out, don’t call attention to yourself,” she said. “I saw myself as a wallflower, which hindered some of my successes.”

Kathleen Niles teaches about internment in her eleventh grade American history and AP U.S. History courses. She herself conducted graduate research on internment, focusing on historical memory.

“Something that a lot of the people I interviewed talked about was this feeling of shame,” Niles said. “We know that they didn’t have anything to be ashamed of, but the accusations themselves that ‘you’re disloyal’, ‘you’re not American’ was really painful for a lot of people.”

Internment also contributed to a rejection of traditional Japanese culture, in favor of assimilation.

“When I closed my eyes and imagined myself I saw blue eyes and blonde hair. Dick, Jane and Sally were blue eyed blondes — those were my elementary schools’ readers,” Dominquez-Yon said. “I knew nothing about [being Japanese].”

Many Nisei parents were also hesitant to teach their children Japanese or give them Japanese first names out of fear of discrimination.

“We spoke in English because that was the language of communication. My parents only used Japanese when they didn’t want us to know what they were talking about,” Dominquez-Yon said. “They didn’t want us to go through the prejudice they suffered.”

Because of this, Yoshimura learned French and Dominguez-Yon learned Spanish instead of Japanese.

“My dad was a farmer and had braceros — Mexican farm workers — in the fields, who would sing and laugh… I wanted to do that,” Dominguez-Yon said. “I considered myself a rotten banana because I was yellow on the outside and brown on the inside.”

In 1988, the U.S. government issued a formal apology for internment and gave each survivor $20,000. The government also acknowledged the event as “race prejudice, war hysteria, and a failure of political leadership.”

Modern Reverberations

2017 marks the 75th anniversary of internment, but many issues present during WWII still exist today.

Many surviving internees stress the importance of activism, protest and standing up for rights. Education is also a key factor in working to prevent another similar event.

“[We are] struggling to get [internment] into history books, struggling to get it onto the table,” Yoshimura said. “People still don’t know and yet it’s incredibly powerful and personal.”

Niles teaches about internment in all of her classes. Her class focuses on exploring why some groups, including the Japanese, are viewed as ‘un American’ and how minorities overcome this. But, she also views this as a cautionary tale.

“I think that there’s always a danger of violating the constitution. We have a long history in this country of national security being threatened, [and] we often respond by saying we can sacrifice individual rights for national security,” Niles said. “It’s always important to look back at some of those decisions from the past to think about what kinds of sacrifices of individual liberty are we willing to tolerate for the sake of national security, and I would hope that internment is something we would not repeat.

Discussion of the internment is especially pertinent in the current political climate.

“Now with the attacks on Muslim identity and membership in this society, there’s a concerted effort and rhetoric in our community of ‘this must not happen again,'” Yoshimura said. “It seemed like a distant possibility — of course it won’t happen again. But these recent years, especially after 9/11 and in our current climate, it’s frighteningly real. The motions that I’m seeing resemble all too closely what happened with the Japanese — the executive order to start it off, the rhetoric of alterity. There are lots of Japanese-American groups having dialogue with Muslim Americans. They’re having joint sessions — it’s really powerful.”

Correction Statement:

(Nov. 24, 2021, 2:45 p.m.): After Meri Onishi reached out to the Editorial Board and expressed concerns regarding clarity, we made the following corrections to the initial article: we updated a numerical statistic that was not overtly specified and also provided further chronological context. We omitted a fragment of a quotation that we felt would not compromise the integrity of the piece. We replaced a previous hyperlink with an updated academic source and revised previous errors in the text itself, as well as in the photo caption.

Kristin Taylor • May 1, 2017 at 10:30 am

Cybele, such a great feature. If you haven’t already seen it, George Takei wrote a powerful op-ed in the New York Times a couple days ago about his own experience in an internment camp and the government’s role in it. Definitely worth a read: https://www.nytimes.com/2017/04/28/opinion/george-takei-japanese-internment-americas-great-mistake.html?emc=edit_ca_20170501&nl=california-today&nlid=68812769&te=1&_r=0

Scott C. Smith • Apr 21, 2017 at 8:07 pm

Cybele,

This is an excellent article. You found people directly connected to the Archer community whose stories and experiences make this history so much more real.

And I very much appreciate how you courageously (but graciously) made the connection to the current political climate.

On both counts, this is what journalism should always strive to do!

Ms. Geffen • Apr 21, 2017 at 5:16 pm

This is a powerful article, Cybele. Excellent work. I learned a lot and appreciated the personal stories you shared. I was especially struck by the impact of Japanese-American internment on members of our Archer and CA community, the severity of conditions in the camps and the lasting sense shame for many families.

Beth Gold • Apr 21, 2017 at 12:31 pm

What a wonderful piece Cybele! Thanks for focusing attention on this sad period of American History, especially at a time when other immigrant groups are being threatened or questioned on their loyalties. As a history teacher, I’m particularly appreciative of your effort in capturing oral histories from our own community members.

Anna Brodsky • Apr 20, 2017 at 5:34 pm

Cybele, thank you for writing this amazing synthesis of research and personal experiences. It was beautifully written and completely opened my eyes to the struggles that the Japanese-American population continues to face. Incredible job!

Alexandra Chang • Apr 20, 2017 at 4:43 pm

Such a beautifully written article, Cybele. Thank you for writing this. Amazing, amazing job <3

Winston Smith • Apr 20, 2017 at 3:56 pm

A very important moment of our nation’s history. A definite black mark that is oft ignored in the interest of feeling good about ourselves. We need always remember and not rewrite history.

Dr. Yoshimura • Apr 20, 2017 at 3:55 pm

Cybele, you have crafted a beautiful essay that gracefully integrates multiple families, major moments, and core dilemmas. It’s a privilege to be part of your article. On behalf of my late father and our entire family, I thank you.

Dr. Yoshimura

Brian Wogensen • Apr 20, 2017 at 10:28 am

Such a thoughtful, well-researched exploration and accounting of the Japanese internment and resonances with our modern world. Kudos.

Isaac Pugh • Apr 19, 2017 at 11:28 pm

Very well-written article on the life of interned Japanese. The inclusion of many sources helped the relatability and reliability. Amazing article.