“The Handmaid’s Tale.” “The Bluest Eye.” “To Kill a Mockingbird.” These are all books that have been challenged or banned across the country, and they are also books taught in English classes at Archer.

According to the American Library Association, “in a time of intense political polarization, library staff in every state are facing an unprecedented number of attempts to ban books.” Additionally, 2022 marked the greatest number of attempted book bans since they started gathering data regarding censorship in libraries over two decades ago.

Preliminary data from Jan. 1-Aug. 31, 2023, revealed a 20% increase from the same reporting period in 2022. The majority of challenges were to books written by or about Black people, Indigenous people and people of color, as well as members of the LGBTQ+ community.

In response to a surge in the number of challenged books in schools, bookstores and libraries, the ALA launched Banned Books Week in 1982. The annual event aims to unite the book community in supporting the freedom of expression, learn about past and current efforts to remove or restrict access to books and highlight the importance of open access to information.

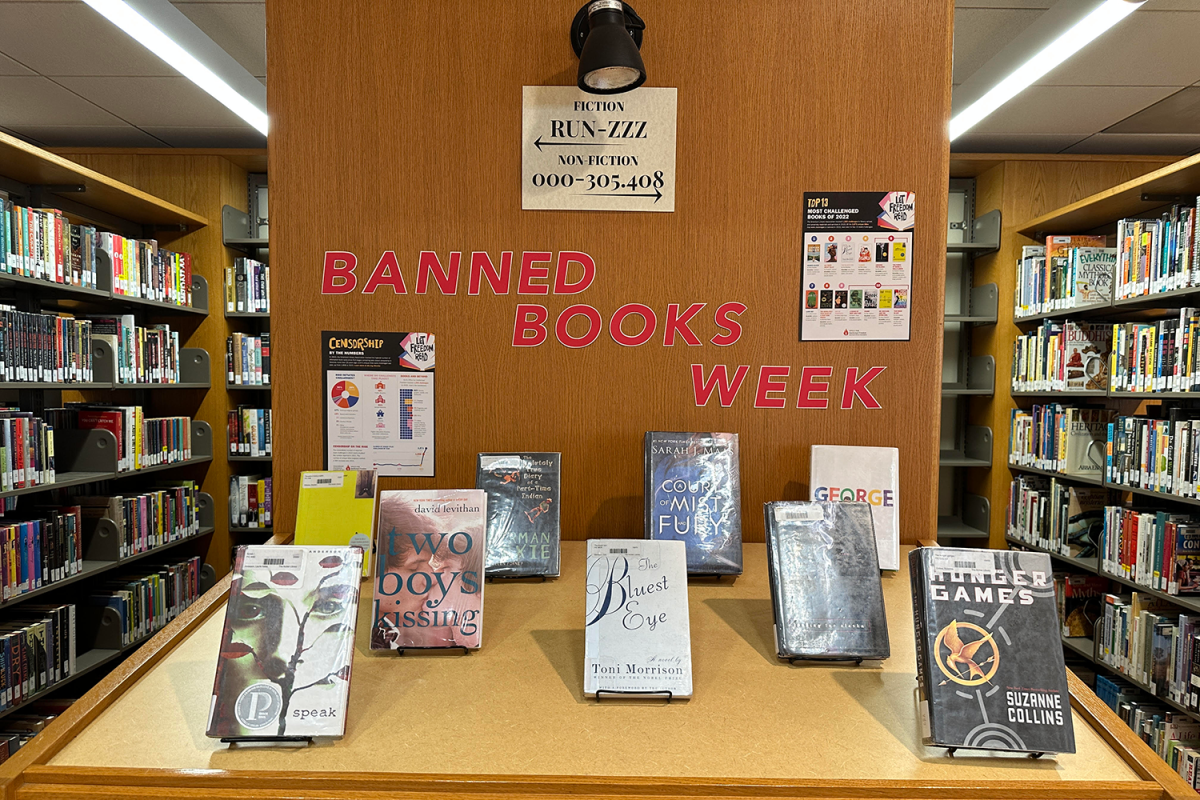

This year’s Banned Books Week spanned Oct. 1-7, and the theme was “Let Freedom Read.” Aligned with the mission of the week, librarian Denise Hernandez displayed books that have been historically banned or challenged in public libraries and schools across the country, including “The Hunger Games,” “The Perks of Being a Wallflower” and “Speak.”

“It’s important for everyone to know what’s at stake sometimes, or at least the privilege that we have here because we’re a private school, and we’re not really subject to parents calling and saying, ‘You need to get this book off the shelf.’ There’s a lot more freedom here — a lot more access to your curiosity and your learning and a lot less barriers from books that they call, maybe sexually explicit,” Hernandez said. “It’s insane because most of the books on [the display] talk about real-life issues, or their allegories and allusions to real-life issues.”

According to a PEN America article, during the 2022-2023 school year, book bans were most common in Texas, South Carolina, Florida, Missouri and Utah. The article also stated that the “implications of bans in these five states are far-reaching, as policies and practices are modeled and replicated across the country.” School districts in different states are responding to new laws that decide the kinds of books that can be in schools and which types of policies they must follow to add new books.

English Department Chair Brian Wogensen said, although book banning has a long history, the recent surge in bans like these further increases the importance of learning the reasoning and effect of these limitations.

“Now more than ever, highlighting the restrictions that are placed on ideas and stories [is important], and I say now more than ever because state governments are now involved in banning books, limiting reading — there’s just a real upsurge in it,” Wogensen said. “It’s important to keep us all thinking about those restrictions and the impact of them and the impact they can have on both dulling us and removing ideas from our world.”

Junior Charlie Clayton ran the Freshmen-Sophomore Book Club last year and said she appreciates having access to books at Archer that have been challenged or banned. Clayton added that she finds it interesting to analyze the recurring themes or ideas present in these banned books.

“We’re lucky to [go to] a school where they put the banned books on the shelves,” Clayton said. “Books are banned for a lot of reasons, but it’s important for students to learn about the reasons that books have been banned … the most important thing [is] developing your own opinions, but making sure that they’re your own and developing a perspective about a book based on your own knowledge instead of it being banned.”

Similarly, Wogensen emphasized the role of literature in providing a wide range of perspectives for students to consider so they can form their own opinions and engage in discourse.

“It gives students the opportunity to make decisions for themselves, to be confronted with diverse points of view and also to do that … in a classroom environment with collective inquiry with the guidance of a teacher who’s helping you explore, consider and digest a text,” Wogensen said. “As you ban books, you’re also banning disagreement, and I think disagreement is actually pretty important to our way of living and considering the human condition.”

The Archer library website showcases information about their current displays and the catalog of books they offer. Hernandez said she does not typically stop any sixth through 12th graders from checking out a book unless it is very inappropriate for their age level, but this does not happen very often.

“The studies show that a lot of people in general have a lot of faith in libraries and in their librarians because we’re so community-centered, community-focused,” Hernandez said. “My goal is that somebody sees the work that goes into the displays for Latinx Heritage Month, LGBT History Month, we have so many [displays] that we’re really lucky to have access to the books that we do.”

Wogensen said he believes teaching these books in a thoughtful way and examining why a book is banned is essential to discuss and understand when engaging with these texts. He particularly highlighted that readers should consider the possible motivations for banning a book and confront or think critically about those ideas.

“As far as banned books go, it’s not like we purposely choose books that are highly banned in the United States and put them on our curriculum … I think it just so happens that quite a few of the texts in our classes have been banned because they have dynamic subject matter,” Wogensen said. “A broader suggestion I have is: just don’t let your curiosity be stifled … read as much as you can, and seek out interesting stories.”