I still vividly remember my sixth grade self peeking out of the plane’s window, watching both excitedly and nervously as we soared over the horizons of Hong Kong. Leaving behind familiar streets and faces, I embarked on a journey to Los Angeles, a city that would soon become my new home. Little did I know, this flight marked the beginning of an exploration of my identity and cultural adaptation.

Growing up in Hong Kong, I attended a local public school where I was surrounded by people of the same race, experiences and background as me, so I didn’t have much exposure to diversity. Our educational system included many lecture-based classes, and we didn’t have many opportunities for critical thinking discussions.

At the beginning of each school year, we were arranged into classes based on our academic grades and were expected to be well-rounded in all types of activities, such as sports and music. This created an extremely competitive environment, as there were many comparisons among students, and it always lowered my self-esteem.

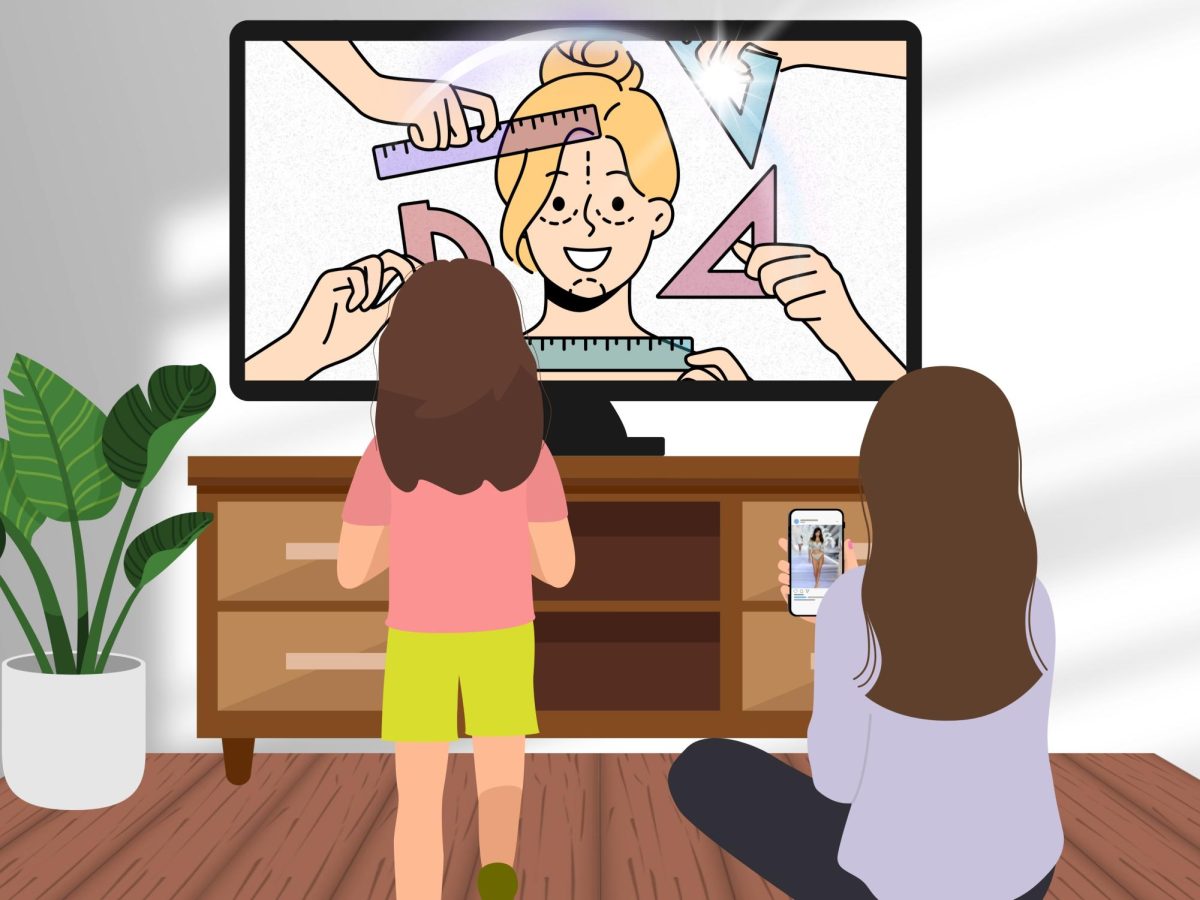

During my first year in the U.S., the COVID-19 pandemic confined me to a virtual realm, leaving me in a liminal state of culture — I was unsure where I belonged within my new community. As time passed, I wanted to become more “American”; I copied the way people dressed and interacted just to fit into society and not seem like an outsider. I completely blocked my Chinese identity out of my mind.

However, my mindset soon changed as I entered my second year of school, and Archer transitioned back to in-person learning. I began to realize how much enthusiasm and open-mindedness my peers brought to class at a liberal, progressive all-girls school. It was nothing like I had experienced in Hong Kong. We engaged in judgment-free discussions and debates, and students were not afraid to voice their diverse opinions, personal stories or backgrounds, making me feel bonded with my classmates like one big family.

Amazed by my peers’ confidence in class, I was inspired to find a voice of my own. This inspiration not only translated to participating in class, but it also taught me to embrace a side of my identity I was drifting apart from.

I am just one of many Hong Kongers who are experiencing cultural assimilation upon moving to a new country. According to The Guardian, the city’s population fell from 7.52 million at the end of 2019 to 7.29 million in mid-2022, as many are immigrating to other countries in search of democratic freedoms.

The exodus of Hong Kong residents is driven by political concerns about the National Security Law China’s government implemented in 2020. This law undermines Hong Kong’s “one country, two systems” policy, established under the Sino-British Joint Declaration in 1984. These policies allowed the city to maintain separate legal, economic and political systems from China, including freedoms not enjoyed on the mainland, for 50 years following Great Britain’s handover in 1997.

The new law grants powers to Beijing to oversee the enforcement of Hong Kong’s autonomy, taking away the city’s civil liberties, including freedom of speech, assembly and press. This regulation led to years of protests, mainly consisting of students, against the Chinese government’s crackdown on pro-democracy activism.

Hayley Ho (’26) recently moved to the UK from Hong Kong, and she is now attending secondary school at Concord College. Ho said her classmates and teachers are welcoming and patient with her, and she feels more confident learning in this type of environment compared to her local school in Hong Kong.

Both Europe and the U.S. have similar social dynamics in schools, such as a focus on mutual support and shared experiences from different backgrounds. However, in Hong Kong, due to its homogeneous population and achievement-oriented culture, competition may play a more prominent role in interactions and friendships.

“I’m definitely more open-minded, and I feel more confident than I was. In the UK, they really encourage you to discuss you’re thinking in groups, so this [move] really helped with my public speaking and social skills,” Ho said. “I had social anxiety when I came here, but my classmates actually put in the effort to try and talk and relate to you, to make you feel comfortable and less pressured. That’s why the friendships here are more genuine.”

Seeing the openness of many of my classmates, who readily share their cultural backgrounds, has empowered me to be confident and do the same. Without the experiences I encountered in Hong Kong, I might never have realized the significance of my own identity. I now love sharing about where I came from and about my Chinese culture, whether the food we eat, traditional clothes we wear or Chinese New Year celebration activities.

I believe everyone is special in their own way, and that’s what makes our American community so interesting. There is no such thing as being “Americanized;” we all have our own customs, values, languages and mannerisms that we develop to form our identity. I feel very blessed to have two homes where I feel accepted. The blend of both cultures is what makes my identity unique.

I’m proud to say I’m a girl with two identities, and I am and will always be both Chinese and American.