There are two likely reasons why an adult or adolescent would read a children’s fairy tale book: either to offer criticism or to find comfort.

Children’s fairy tales are excellent to analyze and look at with news eyes as we get older and learn more about the world; you may understand them in an entirely different way when you revisit them, both your interpretation from childhood and an older age coexisting — something English teacher Brian Wogensen, who teaches the senior seminar “Literature of Fairy Tale & Fantasy,” calls “bifocal reading.”

“[Fairy tales are] so very human, and so we recycle those forms and those narratives, and they’re kind of reinvented for every generation, every age, in different ways,” Wogensen said. “It’s fun to kind of take an old something old and classic and modernize it and use it for satire or for critique.”

Children’s books and fairy tales are a source of comfort and can bring up feelings of nostalgia. In between reading distressing news reports and the intense “Handmaid’s Tale” in 11th grade English class, it sometimes helps to read something that takes you back to a time when you were only vaguely aware of these problems, if at all. Many sources have noted that such stories can help restore hope.

Of course, avoidance and voluntary ignorance are not the solution; hiding is a coping mechanism that should only be used temporarily. And while children’s books give us a warm glimpse into our past, they rarely offer a way forward.

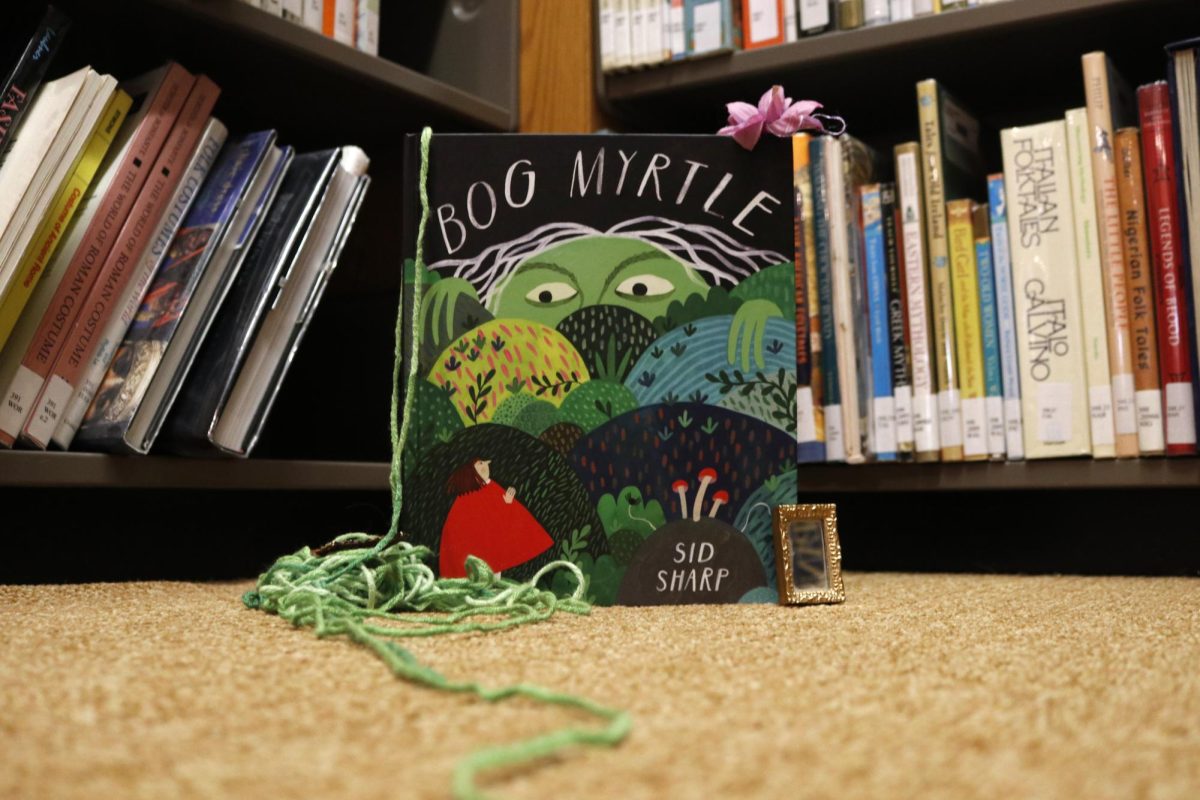

I was pleasantly surprised to find both of these qualities in author and illustrator Sid Sharp’s latest children’s book, “Bog Myrtle.” The story follows two sisters, Beatrice and Magnolia, after Beatrice tries to make a sweater for Magnolia. The two are as different as can be. Beatrice is almost always seen smiling, wearing a cheerful red jacket and looking for ways to express her endless joy. Magnolia, in contrast, has a perpetual, deep frown on her face that is comically extreme. She is said to only be good at bossing Beatrice around.

Both sisters are of unspecified age, characterized by a childlike stubbornness but living “alone in a hideous, drafty old house on the edge of town.” Their situation is a little ambiguous and helps to fuel the cryptic, though non-threatening, world Sharp invites the reader into. As with any fairy tale or fairy tale-adjacent media, we’re encouraged to suspend our disbelief.

The story begins with Magnolia’s ceaseless complaining. She wakes up one day in a bad mood — which is presumably the same way she wakes up every day — because of how cold she was that night. Beatrice decides to make her a sweater, and because she does not have the money to buy yarn, she tries to trade “treasures” she finds in the forest for yarn. She is firmly told to vacate the yarn shop premises.

When Beatrice returns her treasures — such as “the twig from the tallest tree” and “the shell from the shiniest cicada” — to the forest, she is met by a furious Bog Myrtle who seems to be a giant spider creature. Beatrice apologizes for taking the items and explains she didn’t know they belonged to her. Bog Myrtle responds that “the forest doesn’t belong to anyone,” and “we need to leave it better than we found it.” Beatrice apologizes, and the two bond over their love of the forest. Despite appearances, the two have a lot in common. Bog Myrtle gifts Beatrice some of her magic silk so that she can make Magnolia a sweater. That’s all just the first chapter.

Sharp is a phenomenal artist, and the book is filled with enchanting drawings, reminiscent of fairy tale illustrations and Over the Garden Wall. Along with this deceptively friendly art style comes something fairy tales are known for: societal critique. The book quickly explores complex themes such as capitalism, nature conservation and unionized labor. The initial shock and hilarity of such direct references to these topics in what at first glance appears to be a standard children’s book makes “Bog Myrtle” enjoyable for teenagers and adults as well as young children — hopefully passing C.S. Lewis’s requirements. The books is also refreshing because Sharp lets us enjoy an all the benefits of a fairy tale-like story without the sexism and racism that so often accompany the classics of the genre.

As you get older, reading children’s books can also turn into worrying about what the next generation is being taught; “Bog Myrtle” makes me hopeful for the future of children’s literature. It familiarizes younger readers with important lessons: nature is something to “treasure,” apologies are normal, it’s disrespectful to cross a picket line when spiders are on strike and if you disrespect a giant spider she’ll turn you into a fly and eat you. You know — everyday things we are all aware of.

The book is a bit longer than expected, at one hundred and fifty-six pages, which could potentially turn away some readers. There are also a few moments that may frighten or confuse children more than amusing or teaching them, such as Beatrice making a “new” sister out of worms after her old one disappeared. While the book emphasizes sustainability, it avoids diving into some of the scarier aspects of climate change, as the main evils present are one mean sister and a few people trampling plants. I appreciate that this is a gentle way to introduce important concepts to children; I hope older readers will look deeper into the underlying themes of this fantasy.

Even with those small grievances, “Bog Myrtle” is a wonderfully creative novel that builds upon past fantastical children’s stories and illustrations to produce a refreshing and hilarious book. Whether you are 5 years old, 15, 32 or 73 — “Bog Myrtle” is a wonderful book I highly recommend.

-

Writing

-

Story

-

Characters

-

Enjoyment

-

Purpose

-

Illustration

Summary

“Bog Myrtle” is an illustrated children’s book published October 2024. It is author and illustrator Sid Sharp’s second book and covers themes such as sustainability, market capitalism and kindness. The story follows a girl named Beatrice as she sets out to knit a sweater for her sister, whose main joy is making money.

Ms. Hernandez • Dec 16, 2024 at 8:33 am

YAY for picture books!!