When driving down any street in Los Angeles, it is impossible to miss the hundreds of billboards. Among the movie posters and flashy makeup brands lie blatant promotions of high cheekbones and hourglass bodies, all endorsing plastic surgery. These advertisements, consumed by millions of adults, teens and children alike, feed into the numbers of insecurities among individuals, encouraging the same copy-and-paste look.

Every year, 15 million Americans get plastic surgery, and in 2020, 17 individuals died as a result. While 17 deaths may not seem like a lot, the psychological effects of plastic surgery can be detrimental to millions of susceptible youth.

The message that you are only perfect if you are fake saps individuality from people, ultimately creating insecurity around natural beauty. When this is fed to teens’ malleable minds, they begin to believe that they are only beautiful if they are plastic.

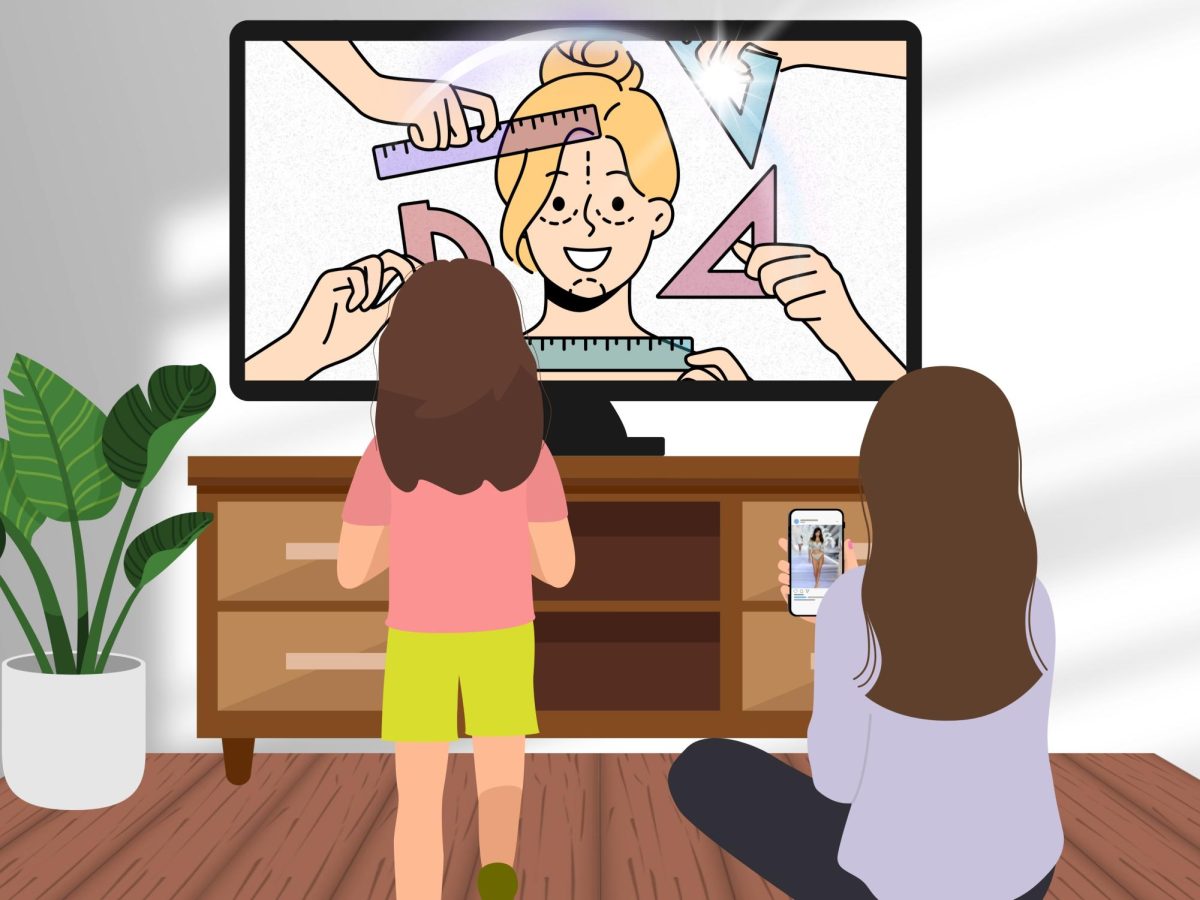

When scrolling on social media, teen girls inevitably come across models showcasing their bodies. Teens naturally compare themselves, feeling a sense of dissatisfaction with what they look like compared to Instagram models. A study conducted by the National Organization for Women found that, by age 17, 78% of girls were unhappy with their bodies. This dissatisfaction could lead teens to solutions that promise quick fixes, such as plastic surgery.

But this so-called quick fix has permanent repercussions, both mentally and financially. When teenagers first leave the house and become financially independent, they don’t have much experience making financial decisions. It is easy to make rash decisions, like getting a rhinoplasty or breast augmentation that they’ve eagerly awaited since their early social media years. These surgeries can range anywhere from $3,000-$15,000. Even worse, surgeries’ effects, such as breast augmentations only last for around 20 years.

A poll conducted by the University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health found that 47.1% of women who got breast augmentations regretted their decision — that is almost half. Some might be disappointed that they hadn’t explored more options or that they chose the wrong implant size. Some might even experience physical discomfort and back pain.

Is that worth the Instagram shot? It’s debatable. If you were to argue yes, the cycle repeats. The post-surgery teen will finally upload that identical photo, which will show up on another teen’s page as an unattainable body, and they will then wait for that surgery.

Although it’s not entirely common, in 2023, 260,851 teens got plastic surgery. While teens normally get plastic surgery to fit in with peers, they also feel left out when seeing plastic beauty on screen. In a world of so many beautifully unique faces, the plastic surgery industry is encouraging specific beauty standards and conformity.

Over time, plastic surgery has become normalized in Western culture to achieve a specific look; however, beauty around the world varies and doesn’t always praise the same face. In Italy, a toned body and high cheekbones are prioritized. In Somalia, they prefer a curvy figure, a slim straight nose and a long neck. In Pakistan, it’s ideal to have thick hair.

With this being said, all of these places still have beauty standards, and plastic surgery seems like an easy way to fit in. While we may be quick to blame teens for wanting to fit into these “ideal” standards, the fault lies in the hands of past generations. But beauty isn’t set in stone — the concept of a beauty standard has been around forever.

Let us go back 25,000 years in Europe to the Paleolithic Era. A statue titled Venus of Willendorf was discovered in 1907. This “Venus” body type emphasized a curvaceous and thickset woman. If we move to ancient Greece, we see Aphrodite depicted with curves. And if we move more recently, Marilyn Monroe was a walking goddess who also happened to be curvy. A pattern arises that showcases curvy bodies being seen throughout generations and around the world, and not only one type.

So, when did this idea of altered beauty begin?

The First World War left thousands of American soldiers with facial disfigurements that incited ridicule and discrimination towards them. On site, they only had unqualified dentists and surgeons to fix their injuries. However, when soldiers returned from the war, they went to two doctors: Vilray P. Blair and James Barrett Brown. The men were visionaries in their field, reconstructing soldiers’ faces and helping them to heal and recover from the war.

The boom of plastic surgery in the late 1980s was due to advances in the field, meaning fewer anesthetics were required and more fillers and laser treatments became available. Facial surgeries then slowly became normalized, shifting from something meant to help people with facial disfigurements into a cosmetic choice.

These alternatives prove that with the advancement of technology comes less-invasive options for plastic surgery. There are, however, disadvantages to using fillers; they migrate over time and can be unreliable. The only upside, I suppose, is that now your lips can look like onion rings.

People around the world have accepted the fact that they have no control over this trending surge in plastic surgery, but that is absolutely false. We can choose what to endorse, what we choose to let children see, and ultimately what we post.

If we promote a culture that prioritizes authenticity over artificiality, we can protect younger generations from the message that beauty is only skin deep. Let us thrive in a future where individuality is not overshadowed by the allure of plastic but where each unique face is cherished.