As a high school student studies for a test, she sits at her desk, shoulders hunched, for hours. Her pencil scratches against the surface of the paper, the candle wick curls, then burns, as time continues to pass. She feels less and less confident as the hours go by; no matter how many equations she attempts to solve, her brain is unable to put two and two together. She knows that it is not due to her lack of comprehension, but rather how her brain processes information.

There are several mental health conditions that lie underneath the neurodiverse umbrella. All of these conditions have the ability to affect cognitive processes and impact our learning styles. Merriam-Webster defines neurodiversity as “the concept that differences in brain functioning within the human population are normal.”

However, I’d like to change one thing to this definition. Neurodiversity is not just inherent, it’s universal. Everyone experiences cognitive differences, learns in unique ways and prefers certain assessment styles over others.

Archer’s curriculum does incorporate diverse teaching methods, but there is still room for improvement. Allowing more flexibility in assessment types for every class rather than defaulting to traditional tests and essays can easily create a more inclusive environment.

Test-taking isn’t the only way to measure a student’s comprehension of material. Essays, paragraphs, projects and in-class discussions can also accurately assess understanding. However, teachers preferring one assessment method over the others can quickly lead to an imbalance in evaluating a student’s true grasp of a subject because different learners excel in different class formats. With neurodiversity, students with varying cognitive styles — such as ADHD, dyslexia or autism — can struggle with tests but thrive through other assessments, such as projects or Harkness discussions.

Learning Specialist Danit Kaya said that 20% of Archer’s population is neurodiverse, and traditional teaching styles can create barriers for these students. However, by including multimodal forms of instruction — such as visual aids or slides that go hand in hand with lectures — students are able to participate and learn more effectively.

“If we make the curriculum accessible to neurodiverse students, we’re actually providing a more robust curriculum to all students, regardless of what their learning profile looks like,” Kaya said. “It’s a way to make sure that students can access the curriculum whether they have a diagnosed learning difference or not.”

Abby Morrison (’29) agreed and said that she’s received a lot of Claim-Evidence-Reasoning paragraphs throughout her middle school experience.

“In seventh [grade], we learned how to write a CER in history, English and science —basically, all the academic classes. Every test is pretty much a CER, and CERs aren’t always the easiest way for people to show their understanding,” Morrison said. “Fifty percent of the class might get good grades, and the other 50% of the class may not even if they have the same understanding as the people who got good grades. It’s just because CERs aren’t a way they can show it as well.”

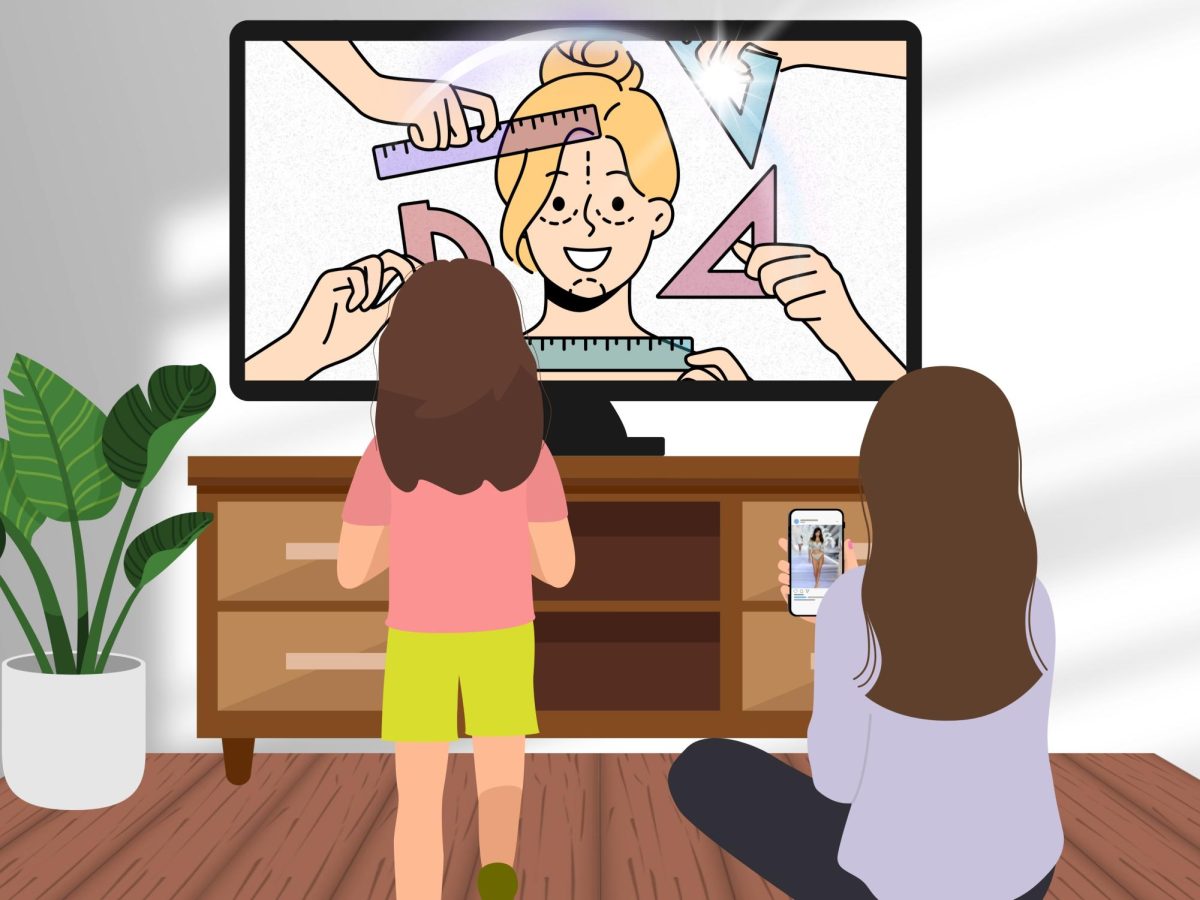

Repetitive assignments like CERs do not truly assist a student throughout their educational career. CERs or essays might provide important skill sets for later in life, but consistently choosing the same type of assignment over and over again only removes one’s access to different skill sets through other learning methods. For example, writing essays and paragraphs might develop communication skills and research abilities, but there are other assignments — such as creating an infographic or poster — that can achieve the same end result and also teach graphic design skills and organization. If a student is only focusing on developing these particular assets, their learning is not well-rounded. Reinforcing a narrow view of what “success” looks like ignores the diverse ways in which students process their knowledge.

Oftentimes, final assessments fall under the test-taking or essay-writing category and are worth 10% of the grade or more. This is limiting for students who have learning differences, for which tests and essays may not be the most effective way to showcase their understanding of the designated material. By relying on these types of assessments, we undermine students’ individual and creative strengths.

Alternative forms of test taking — even for finals — should be available for every assessment, and the student should have the priority of choosing what method works best for them. This not only promotes healthier learning but will also contain more accurate reflections of a student’s comprehension and academic abilities.

Accommodating one difference with one solution, such as extra time, shouldn’t be the baseline for the school curriculum because it doesn’t accommodate all neurodiverse students. Embracing the various ways people learn is equally as important. By including assessments that can support a variety of different needs, every student — regardless of how their brain functions — is able to thrive.