Every day, Archer girls and their parents can log on to the online gradebook site “Haiku” to check the status of their classes and see if any updates have been made. But opinions about the gradebook are varied.

The purpose of the gradebook is to provide students with real time access to their grades in addition to keeping parents informed. Some students feel that the gradebook is an excellent tool that enables them to understand their position in classes. Other students see it as a source of conflict with parents in their home lives.

The Oracle sent out a survey via email to members of the Archer community grades six-12. One hundred and fourteen students responded out of 481 students, leaving a margin of error of eight points with a confidence level of 95 percent.

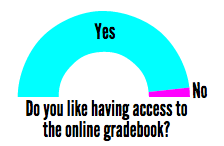

The survey revealed that the vast majority of students, 96 percent, like having access to their grades.

“I think it’s nice because I don’t have to wait every quarter to get my grades, and I’m able to check my progress and keep myself in check,” Leandra Ramlo ‘16 said.

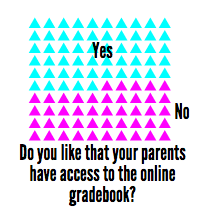

Students were divided when it came to whether they liked that their parents had access to the gradebook: 54 percent of students reported liking that their parents can see their grades and 46 percent said they do not.

Upper School Director Samantha Coyne-Donnel explained the mission of the electronic gradebook.

“I think the goal of moving to an online grade system is that this is the 21st century,” she said. “We want students to have that real time access to feedback and to their status and their progress.”

“We also thought it was challenging sometimes to communicate with parents about grades within a timely manner but this just takes that layer away,” she said. “We did a lot of parent education saying ‘this is really your daughter’s journey,’ and especially in Upper School I would say we want students… to go to the teacher or me or their advisor and navigate the process… independently.”

Ramlo doesn’t mind that her parents can see her grades.

Ramlo doesn’t mind that her parents can see her grades.

“My parents don’t really check my grades — it just doesn’t occur to them — but I’m sure it varies from person to person,” she said.

Another junior shared her experience with the Oracle. She asked to remain anonymous so as not to create conflict in her family. Although she shares Ramlo’s graduation year, her experience with the gradebook is very different.

“I think that it just feels like my parents are way too involved and don’t trust that I can handle my grades,” she said.

The gradebook has caused a lot of arguments in her household.

The gradebook has caused a lot of arguments in her household.

“It’s not a constant thing,” she said, “but it will sometimes be kind of passive aggressive like ‘oh I noticed that your grade in math has dropped, did you do anything?’”

She said her parents tell her that her grades will affect the college she will get into, so if she doesn’t turn things around she will need to adjust her goals.

“I think at this point — I can maybe understand if you’re in eighth grade — but I feel like at this age we want to do well for ourselves,” she said. “And I think that most people are motivated enough to want to do well in school and even if you don’t I feel like at this point it’s our responsibility and it shouldn’t have to be our parents.”

She sees value in parental access for less motivated students, but even so, she feels that Archer is on top of it enough without parental access.

“I think having your advisors being able to see your grades is a good thing because they won’t be that involved in your grades unless they need to and if there is really an issue… then that’s when you contact Ms. Coyne and your parents and have a discussion about it instead of having parents constantly stalking your grades,” the source said.

She also thinks it won’t prepare students for college, where teachers are not constantly checking in with students.

“If you’re in a huge class like most freshmen are at some point with 200 people or something, your professor isn’t going to personally find you if you get a bad grade on a quiz or test so at that point you have to decide what your goals are,” she said.

Coyne agreed that college is a different situation when it comes to gradebook access.

“It’s the opposite when you go to college; generally you have no idea where you stand until the final grade comes out but I do think at the end of the day we should be informing [Archer students]—our students should know where they stand.”

Coyne explained why Archer made the choice to have parents see grades: “We just felt like it was in everyone’s best interest to be completely transparent and then try to educate about how to have a healthy perspective around grades and progress,” she said.

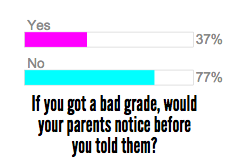

“Surprisingly, we thought that we would open it up and all the parents would be sitting online and checking in, but the reality is that isn’t happening and that’s why we still email out about academic alerts if there’s a concern about a student performance because we know that a lot of parents are trusting their daughters or checking on occasion,” Coyne said.

English teacher and Archer Alumna Kate Webster has experienced both sides of gradebook access. She described the system that was in place at the time she attended Archer to the best of her memory. Webster graduated in 2007.

“We would get printed out tri-weekly reports so every three weeks we would see an update of our grades,” she said, “which wasn’t entirely effective because by the time we got our print out, the grade was probably not up to date anymore but on the other hand it meant that we weren’t constantly checking our grades and our parents weren’t constantly checking our grades.”

Her own experience was closer to Ramlo’s than that of the anonymous junior.

“My parents were very hands off,” she said. “The responsibility was always very much on me, and I really liked it that way. I think it should be the student’s responsibility to have that motivation.”

“I had friends whose parents would call the teacher or want to talk to the teacher about the grade. I think that probably happened less frequently than it does now since [parents] didn’t see [the grades] constantly,” she said.

Webster sees pros and cons to each type of gradebook system.

“I definitely think [the current method] increases the stress level of students to be able to constantly access their grades and they always want to know and have that constant feedback,” she said. “But, on the other hand, I think there is a benefit to having that feedback because then you’re able to correct certain behaviors or locate areas for growth sooner rather than later. It gives you more time to correct those behaviors than you might have before.”

“In my own advisory, if a parent sees something in the gradebook, it gives the student sort of less room to hide because there is that level of transparency, for better or for worse,” she said.

Another issue brought up in the survey and in interviews was that some parents can have a basic misunderstanding about the gradebook.

“A lot of parents don’t know how to use it so if a teacher puts in an M and your grade drops from like an A to a B because of one F that isn’t even real they’ll flip out,” Webster said.

“I want students to be focused on learning more so than grades, so grades should reflect what students learn… I think my hope is that allowing for more accessible feedback that is in one place [will allow them to] look back and track what areas they’ve grown,” Coyne said.

Many students in the survey also commented on the fact that they did not like the fact that Haiku sends an email to parents whenever a grade comes in, or even an assignment.

“Haiku sends weird updates to my parents, so they get stressed about tests that I don’t have for another 2 or 3 weeks, that the teacher has just uploaded in advance. It’s super annoying!” one student said.

Jolina Clement, Director of Educational Technology at Archer, works to implement meaningful technology usage at Archer. The usage of Haiku falls under her domain. She does see some potential harms in gradebook usage.

“If it is examined too critically, it can potentially be dangerous. For example: many teachers will take time to grade projects, or log things like participation points at the end of a semester, which can have a seemingly deleterious – yet temporary – effect on a student’s grade (especially early on in the term),” she said in an email interview.

![Science Fair students Sabrina Rifkin ('28) and Jaya Srinivasan ('28) discuss their experiments in class. "I think [Science Fair] is fun," Rifkin said. "I'm definitely more in it, not for the competition, but for the experience."](https://archeroracle.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/MG_9909-1200x800.jpg)