Column: East L.A. Walkouts 50 Years Later

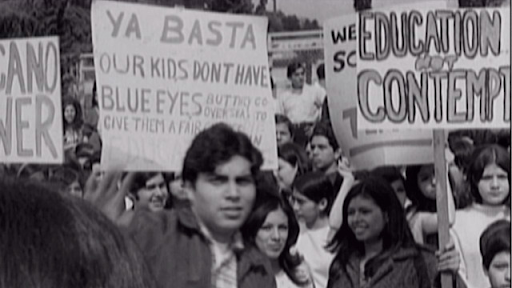

A promotional image of students at a Los Angeles walkout in 1968. Students demanded quality education and to be treated fairly. Image source: PBS.

As I have grown up, I’ve only heard bits and pieces about what high schoolers did during the Chicano Movement. Like most people, I’ve always heard about the more well-known parts of the movement such as Cesar Chavez and the United Farm Workers Union — but I never heard of the walkouts that took place in Los Angeles, which have been mentioned all of two times in my history textbooks. However, in light of the #ENOUGH walkout that happened last month, I was inspired to look into this event.

Every time I read a new article or watch another video, I become more and more fascinated with this radical event. It is officially known as the East L.A. Walkouts or Chicano Blowouts, where hundreds of students all over Los Angeles protested and demanded a quality education. This past Mar. 5 marked the 50th anniversary of the event.

A particular source I was introduced to was a documentary-like video from the Public Broadcasting Service [PBS]. The video showed actual footage from the event and interviewed people, who were actively involved. As a Latina, it made me very emotional, seeing everything that Latinx high school students before me have gone through. It caused be to reflect on the fact that I didn’t know enough about this. It made me feel uncomfortable, guilty and proud all at the same time. To think that a little over 50 years ago, what I get to do, going to Archer and the opportunity to get the education I am receiving, seemed nearly impossible to students just like myself.

The video showed me that in the 1960’s, our education institutions systematically would put Latino students at disadvantages and treated them differently than their white counterparts. It was common for Latino students to drop-out, be forced into the lower quality schools and tolerate the poor treatment from their teachers. It was simply “how things were” and were deeply implemented into our society, which is why most people didn’t think twice about it. Many Latino high school students were encouraged into industrial training as opposed to going to college and making a career, enforcing this harmful message even more.

A real life example of this in the video was a white teacher telling his Latino student, whose parents worked in cheap labor and construction, “That’s a very honorable profession, you should follow in your father’s footsteps.” There was even another girl whose teacher told her, “Oh Paula, why are you even bothering. We all know you’re not going to go to college. You’re going to be pregnant by the end of summer like the rest of your girlfriends.” These students were set up for failure even with things that were out of their control.

A figure who worked tirelessly to change these patterns was Sal Castro, a former teacher at Belmont High School and a fundamental leader in the East Los Angeles high school walkouts. Throughout Castro’s career, he constantly wanted to improve the services given to Mexican-American students, starting in the classroom and then making his way towards conferences and activists groups. Around this time, more students than ever had started to actively speak about Mexican-American education and tensions rapidly increased. Their breaking point was near.

The series of walkouts began, but these boycotts themselves were not always peaceful and smooth; they could rapidly become dangerous. At many occurrences, such as at Roosevelt High School, police were sent to control the scene, which quickly became violent, disappointing chaos.

Students just like me had to go through so much to get their rightful education. Because of where they were from and what society wanted them to be, they were denied equal schooling and were pushed the other direction. Chicano students didn’t care if they were being “disruptive” or “rebellious” because they were taking a stand.

As a teenage Chicana, this walkout fills me with so much pride and empowers me in so many ways. I will continue to educate myself more on this topic, read more articles, watch more documentaries, etc. because there is so much more to it. This is an event that, as young people, I believe we should all take inspiration from and connect to on some degree.

The power we have is sometimes more than we think, and — in times like the one — we must use this power in the best way possible. Thus, I ask my Archer community to find more resources: watch movies such as HBO’s Walkout and read the article the Los Angeles Times published recently.

Lastly, I just wanted to share about what walkouts mean to me. Many high school students around the country have been rallying, marching and walking out against gun violence recently, which in my opinion, is taking productive action. Walkouts to me are a way of saying “no more” — where we stop the routine of our lives and stop the cycle that is allowing these horrendous things to happen. People are tired of what is going on and cannot simply stand idly by. Our voices are precious and a flame will not start without a spark. No one will hear us if we stay silent.

I am so proud of Chicano brothers and sisters, who set an example for me fifty years ago. The powerful voices, who I look up to with adoration, give me the strength to speak my mind now. They worked to the death to give me the opportunities I have today, and the least I could do is use those opportunities. I am so proud of the dedication my generation has and the fact that they will walk out beside me.

Celeste Ramirez joined the Oracle as a columnist in 2017 and is now the Multimedia Editor. Her column focuses on diversity at Archer, highlighting the...

Madison • Apr 23, 2018 at 4:30 pm

WOW Celeste! What a great article! Learning about those who came before us is so important and really inspirational. It’s amazing to see what students, especially students of color, have done to take a stand in our country and our city in the past and make connections to current events 🙂