Column: The end is never

Photo credit: Paulina DePaulo

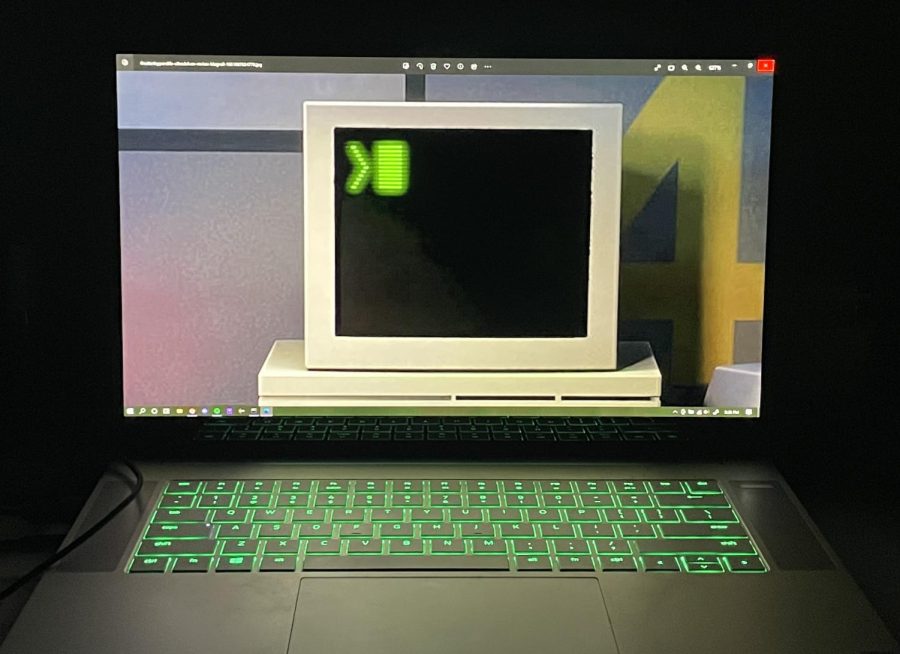

Displayed is Stanley’s computer that he uses during his office job at the beginning of “The Stanley Parable.” The story game follows Stanley on one peculiar day at work when, all of a sudden, his coworkers disappear.

December 15, 2022

This is a story of a man named Stanley. Stanley worked for a company in a big building where he was Employee Number 427. Employee Number 427’s job was simple…

…until it wasn’t.

The Stanley Parable, brought to life in 2013 by the infamous Davey Wreden and featured in my October column, is probably the most confusing game I’ve ever played.

It isn’t that it’s particularly hard to control or difficult to navigate — it embraces the conventional “choose your own adventure” story game formula — but the story itself is anything but typical.

You, the player, are Stanley. Confined to your cubicle in room 427, you work the most mundane office job fathomable, only tasked with pressing keys on your computer keyboard at random intervals. One day, you notice that everyone in your office building has disappeared without a trace. S0 you walk out of your room and start to explore.

Throughout the entire game, your actions and choices are narrated by an omniscient male voice that will try to interact and communicate with you. Your first decision, for example, arrives on your way to the office’s meeting room. You hear, “When Stanley came to a set of two open doors, he entered the door on his left.”

I, of course, entered the door on the right. To my surprise, the narrator corrected himself, speculating that Stanley must have “lost his way to the meeting room.”

Suddenly, in the midst of this low-resolution office building, I was completely immersed in the world. Wreden’s unique narration in both of his original games establish a colloquial connection between the player and the story, eliciting reactions in the most authentic way. I felt as if I had full control over Stanley’s adventure, even when I knew I was already on a predetermined path.

Like most indie story games, each decision you make results in a different ending. From the moment you choose between the left and right door, you’re set down a path that will result in one of 19 final scenes. I later figured out that the choices I made during my first playthrough would result in what is called the “Museum Ending.”

Minor spoiler warning: this is one of the four endings where Stanley dies. However, I’d argue that this is the most interesting one of them all.

In this ending, you wind up stuck on a machine conveyor belt, inching slowly toward a giant crusher. Seconds before death, the crusher suddenly halts, and you’re teleported to a gorgeous museum, filled with homages to the game, relics from Stanley’s life and Easter eggs from Wreden.

I was pulled from the game entirely, almost as if it was never meant to be a game at all. As if, even with the 19 endings, I was meant to end up here, among the blinding white walls and classical music.

But this utopia doesn’t last for long. You’re soon right back where you were, moments before your crushing fate. The narrator, who’s now a woman, urges you to press escape and quit the game altogether.

“There’s no other way to beat this game. As long as you move forward, you’ll be walking someone else’s path. Don’t let time choose for you! Don’t let time—,” the narrator says.

Before she finishes her sentence, you, Stanley, are crushed to death. The game ends, but it remains on an empty black screen until you, eventually, are forced to quit the game altogether. No restart button, and no “game over” screen.

What do you do when it’s all over?

Stanley’s story perfectly encapsulates the existential dread of living, working, loving and dying. It grapples with the darkness of humanity in a humorous way, and still remains deeply profound and, as always, utterly perplexing.