Teenage girls reflect on diet culture on social media in all-girls environment

Photo credit: Olivia Hallinan-Gan

An image of a phone with numerous searches for how to fix one’s body demonstrates social media’s deeply-rooted diet culture. According to Healthline, there was a large user growth among girls ages 15-22 on TikTok, an app known to spread misinformation, especially about weight and dieting. (Graphic Illustration by Olivia Hallinan-Gan)

May 19, 2023

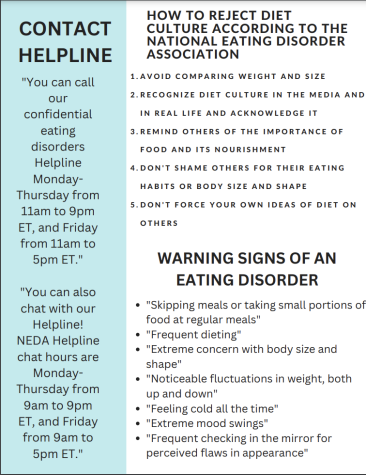

Content Warning: This article mentions eating disorders. If you or anyone you know needs support, reach out to The National Eating Disorders Association by calling or texting 800-931-2237.

*Names Valeria Oliver and Rose Mason are fabricated names to protect the privacy of anonymous sources.

Valeria Oliver wakes up in the morning, and the first thing on her mind is how bloated she looks. She checks to make sure her skirt is able to roll up two times; if not, her waist is not small enough. She adds compression shorts under her skirt to make sure her stomach is tight. She skips breakfast and goes straight to class because that is what she is taught by her family, friends and social media.

According to the National Eating Disorders Association, 35% of dieting becomes obsessive, and 20% to 25% of those diets turn into eating disorders. Additionally, the National Institute of Mental Health stated that 2.7% of adolescents ages 13-18 have eating disorders, it is twice as prevalent in women than men and the prevalence of eating disorders increases with age.

Diet Culture in the Media

According to the University of Arizona, diet culture is “beliefs about bodies and the desire to lose weight that can impact a person’s behaviors.” Dietitian and nutritionist Mascha Davis said she believes diet culture mostly incorporates fad diets, which are mainly seen on social media and aren’t supported by actual sciences. She said even diets meant to counter diet culture are still a part of it, like mindful eating, which is the “act of being present when eating or drinking,” according to Very Well Mind.

“Diet culture includes different fad diets and detoxes and these different trends that are happening,” Davis said. “These diets are out there and not necessarily supported by science or promoted by legitimate experts. There are a lot of specific diets, like the Keto Diet and the Carnivore Diet, so diet culture encompasses all of them — even diets that counter many of these trends … like mindful eating.”

The largest way these diets spread is through media, according to Healthline. Specifically, TikTok, an app that is known to spread misinformation, had a user growth of 180% among 15 to 22-year-olds during the pandemic. In a 2022 study done by the University of Vermont, researchers found that the notion that weight equates to overall health is widespread on TikTok.

In a 2010 study of American elementary school girls who read magazines, 69% said the content shaped their idea of the “perfect” body, and 47% said the magazines made them want to lose weight. People ages 8-18 engaged with media for about 7.5 hours, which was typically watching television and playing video games, where the “thin ideal” is prevalent and can lead to body dissatisfaction.

According to the University of Vermont study, most women glorify weight loss and dieting. The National Eating Disorders Association links body dissatisfaction, disordered eating and the idea of being a thin woman to mass media. Additionally, there is a significant amount of diet advice on social media, and Davis said this advice frequently comes from influencers with a substantial following.

“Social media is definitely good and bad. It’s easy for anyone to become an influencer, and it’s given this platform to people who are not credentialed legitimate experts,” Davis said. “Now, any random person can put out information, and a lot of people — especially young people — may not understand you need to have credentials in order to be someone that should be believed.”

Senior Meera Mahidhara read “The Bluest Eye” by Toni Morrison in her 11th grade English class: Literature of the American Self. For her synthesis paper, she decided to compare the subconscious battles people with eating disorders experience with external beauty standards in the book. Mahidhara said she did extensive research on dieting and eating disorders and agreed social media can worsen comparison.

“I found [that] during COVID, a lot of girls were developing eating disorders because they were looking at social media, and they didn’t have a whole range of different body types,” Mahidhara said. “Everyone looked at social media to get ideas of what’s socially acceptable — what’s beautiful and what’s perfect. Social media is an outlet for a lot of comparisons, body image and diet culture. Now [that] we’re out of COVID, it’s been nice, since a lot of girls have been seeing different people and different identities, but also social media hasn’t really changed.”

Diet Culture in Schools

Educational institutions are another setting where diet culture is promoted. Many schools follow the CDC’s program called the Health Education Curriculum Analysis Tool. HECAT has different objectives for schools including that by eighth grade, students should be able to “explain various methods available to evaluate body weight.” According to a New York Times article, HECAT teaches students proper nutrition but also perpetuates unhealthy ideas and diet culture.

Archer student Rose Mason considered the difference between an all-girls school versus a coed education based on comparison and diet culture. She said comparison and diet culture is much more intense at an all-girls school compared to a coed school.

“A lot of times, [schools] pretend to be so inclusive and like everyone fits in,” Mason said. “Everyone is going to look at each other differently and want to look like someone else. There are also cliques and groups, so if there’s a popular group, all these girls are going to want to look like them. Being surrounded by so many girls who also might have these thoughts just intensifies them.”

Oliver recalled a time when she was at a swim meet and had to step out of the pool because she was shaking. She said she told the lifeguard she didn’t eat before practice, and he was not surprised she went to an all-girls school.

“I was at swim, and I had to get out of the pool because I was shaking,” Oliver said. “I had to tell my coach I hadn’t eaten before the practice, and he then asked me why. I just said I didn’t have time. The lifeguard then asked what school I went to. I said Archer, and he responded immediately saying he knew it would be an all-girls school and wasn’t surprised. I was very caught off guard because I didn’t understand how he could assume from me saying I hadn’t eaten.”

Fitness and wellness teacher Natalie Chambers teaches ninth grade Human Development. She said she cannot control how people perceive the information she gives them about nutrition, but she tries to leave a positive impact on students.

“Everyone’s on their own personal journey when it comes to nutrition,” Chambers said. “Sometimes, it’s that information piece where they’re like, ‘I didn’t know that.’ Then, there are some that struggle with the information that’s presented, and it negatively impacts them. That’s their journey, and I have to respect that I can give the information and leave it with a positive message, but I don’t have control over how they perceive it.”

A study done by the International Journal of Epidemiology found eating disorders increased in girls who attend schools with larger populations of girls. A girl who attends a school with a 50% girl population has a 2.1% chance of developing an eating disorder, whereas a girl who attends a school with a 75% girl population has a 3.3% chance of developing an eating disorder.

Mason said she has witnessed classmates comparing themselves to one another. She said most comparison centers around body size, not necessarily comparing what food you eat to what someone else is eating. She believes these comparisons stem from diet culture circling around school or online.

“I hear all the time, ‘I wish I could wear that top but I can’t because of my arms or my stomach’ or, ‘I wish someone could see my ribs when I stretch,” Mason said. “People talk about how they’ve gained 5 pounds, and it’s triggering. You have to worry about everyone and question whether they might be struggling with their body and eating. I go to an all-girls school, and almost everyone has had similar experiences relating to their bodies. I see it through everything and hear others talking about diets they’re on or see diets on my TikTok I ‘need to go on.'”

Combatting Diet Culture and Eating Disorders

According to NPR, the best way to dismantle diet culture is to recognize that thinness and health are not the same. Many fear being fat, and this causes fatphobia and reinforces diet culture. NPR states that people must remember that their words matter, and, many times, people do not realize what they are saying fortifies diet culture. Lastly, registered dietitian Ayana Habtemariam says that intuitive eating is the practice to help you understand your body and reject diet culture. She also says intuitive eating is simply “learning to understand our bodies and prioritizing body knowledge over external rules like calorie counting and portion sizes.”

Davis said to help teen girls with fears of food, they must reject all myths and misconceptions about diet. She said everyone’s diet is different, and fearing certain foods isn’t healthy for anyone, not just girls.

“Teens need to recognize what makes them feel good and energized,” Davis said. “I think, especially for a lot of young women and teenage girls, helping them to dispel some of the myths and misconceptions that they may have heard is helpful. It’s important to figure out what are some of the things they have heard that they may be following that aren’t true and aren’t healthy for them. It’s actually more about going back to the basics and eating foods that you really love and enjoy. Foods that make you feel really good and getting connected back to what’s nourishing versus getting caught up in what diet culture tells you.”

Chambers said the Human Development department tries to stay away from saying “dieting” when teaching nutrition, and she tries to dispel the notions regarding “good” and “bad” eating.

“We try not to use the word ‘dieting’ because it comes with a negative notion,” Chambers said. “Nutrition is definitely a work in progress as far as what’s happening within our department. We want to try to teach girls and our students that moderation is key. We don’t like to shame or say that one food group is bad or good. We try to talk about how portion control is important and how to read nutrition labels properly. We want to get rid of that negative mindset of ‘this is bad food.'”

This video contains an anonymous interview with Rose Mason, who attends Archer. She speaks about the struggles she has attending an all-girls school and what she has witnessed on social media and at school relating to diet culture. This video also shows students scrolling on social media and the entire feed featuring diet advice and pro-eating disorder content.