Photos are supposed to be visual representations of the past, but what happens when they stop being authentic, especially in a society that is increasingly reliant on visual information to communicate, learn about current events and operate in everyday life?

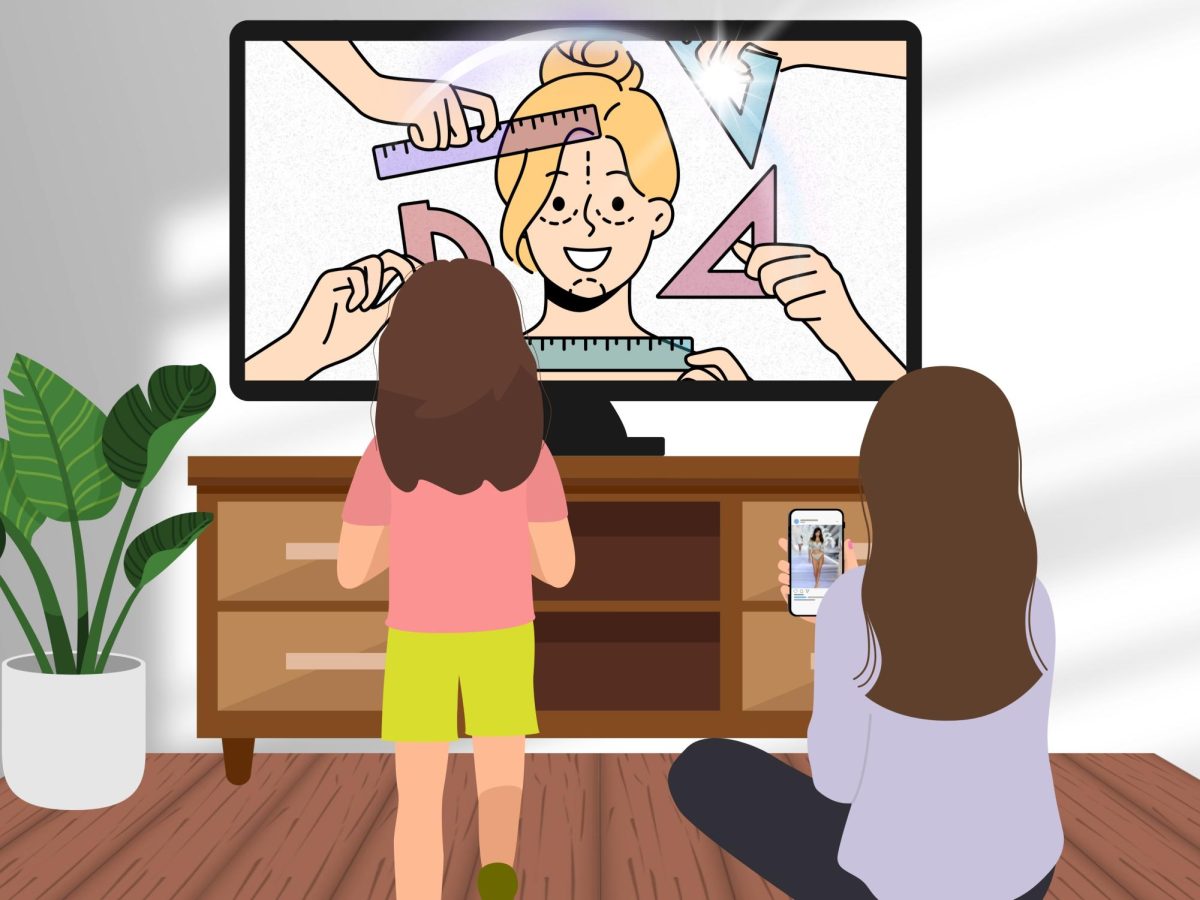

Social media apps like Instagram, Snapchat and Facebook, whose primary format of content is photos, have more potential than writing-oriented platforms like news sites to share fabricated realities that twist the image of society online. Current events and emergencies are now at risk of being incorrectly interpreted by the masses, with misinformation spreading like wildfire. But why would a photo stop being a reliable artifact?

This question, as well as photography’s potential to fabricate as opposed to capturing reality, has been gaining traction due to recent strides in the field of AI-powered photo editing. Google released its newest phone, the Pixel 8, this October; this model is the first mobile phone to implement AI in its default Photos app free of charge. Now, people with technology as common as a cellphone can have control of AI at their fingertips, ready to change any picture and able to contort any photographic story.

In a review of AI photo-editing conducted by the New York Times, Lead Consumer Technology Writer and Tech Fix author Brian Chen found the new $700 device incorporates a generative AI called the Magic Editor, which, unlike regular photo editing, is capable of creating and removing elements by itself, like a person’s face or an object. There’s a “regenerate” button if a user finds the initial results unsatisfactory, as the results have been, according to Chen, “hit or miss.” When Chen wanted to remove a stray piece of paper from a photo of his dog, the software accomplished the task. However, when the Magic Editor attempted to generate that same dog’s entire face, he said “the A.I. produced something nightmarish.”

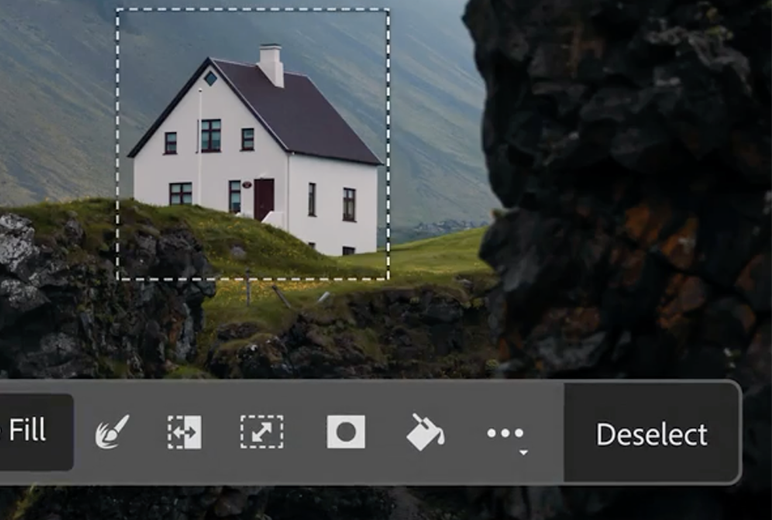

AI is expanding to photo editing services too — early this year, Photoshop created its first generative AI, a beta feature called Generative Fill. This tool, like Google’s Magic Editor, can generate imagery for any photo. All one needs is a computer and $10-20 per month.

As far as this AI photo editing trend goes, New York Times Opinion columnist Farhad Manjoo has declared the technology “good enough often enough.” The strengths of AI photo editing like lighting, scale and perspective coexist with its weaknesses in completing specific requests.

The idea of AI becoming a mainstream part of photo editing sounds great in theory: It can easily remove blemishes and tailor any picture in a way that computational tools could never. But this new editing freedom ushers in a new era of distrust in photography. With AI editing’s increased presence comes a wider range of photos that people should begin questioning.

Another concern is the photo edits themselves. In July, upon “Barbie’s” release, Buzzfeed created a series of 195 images, each depicting a Barbie that was supposed to represent a specific country. Rest of World reporter Victoria Turk found that many of these representations were deeply stereotypical, and this one-sided outlook doesn’t just appear in generating people. When Midjourney was tasked with generating images of particular locations, Turk said “most of New Delhi’s streets [were] polluted and littered,” “in Indonesia, food [was] served almost exclusively on banana leaves” and “some of the houses in India looked more like Hindu temples than people’s homes.”

Now, imagine this same tool spreading its problematic perspective and flawed pattern recognition on cellphones that can post to social media platforms or mainstream websites. With our visual records becoming extremely vulnerable to edits, we can no longer count on our history being told exactly the way it happened.

While the development of AI photo editing is not yet fully fledged, especially with the technology’s novelty, it is gradually making its way into daily life and thereby challenging how we perceive photography. I have grown up in a generation reliant on photography to capture every moment, even going so far as to channel my passion for photojournalism into my work on The Oracle.

So to encounter interference with photography from a faceless, unfeeling tool deeply worries me. The lens through which we all see our world and its past is no longer in our complete control. I challenge people to savor authentic photography while we can, and even in this period of transition, to not be swayed by the convenience and novelty of AI. After all, our memories alone are unreliable and fleeting, but photography remains forever.

Siena Ferraro • Dec 12, 2023 at 4:32 pm

Insightful column, Allie! I always look forward to learning from you.