In the last three months, TikTok videos containing the hashtag “#lettertoamerica” have skyrocketed in popularity, acquiring over 14.2 million views. Written by Osama bin Laden, the letter is a persuasive piece that defends the 9/11 attacks and accuses Americans of being “‘servants’ to Jews,” according to New York Times business reporter Sapna Maheshwari. This letter is anything but patriotic; a man who attacked our nation should never be a source of inspiration for America or its people.

The “letter to America” has not only circulated TikTok but reached and changed its users’ minds for the worse. For example, according to the New York Times, one user claimed they “realized everything we learned about the Middle East, 9/11 and ‘terrorism’ was a lie” and that “America was a plague on the entire world.” The hundreds of thousands of likes attached to the TikToks didn’t help either. The letter is just one example of social media’s alarming rise in antisemitism since the start of the Israel-Hamas War.

Recently, antisemitic hate speech has been rampant on a variety of social media platforms, ranging from mainstream sites like Instagram and Snapchat to fringe sites and messaging apps like BitChute and Telegram. According to Sheera Frenkel and Steven Lee Myers of the New York Times, the amount of antisemitic content rose 28% on Facebook and 919% on X within the first month of the war. On X in particular, figures of power such as Elon Musk have been some of the biggest promoters of antisemitic hate speech.

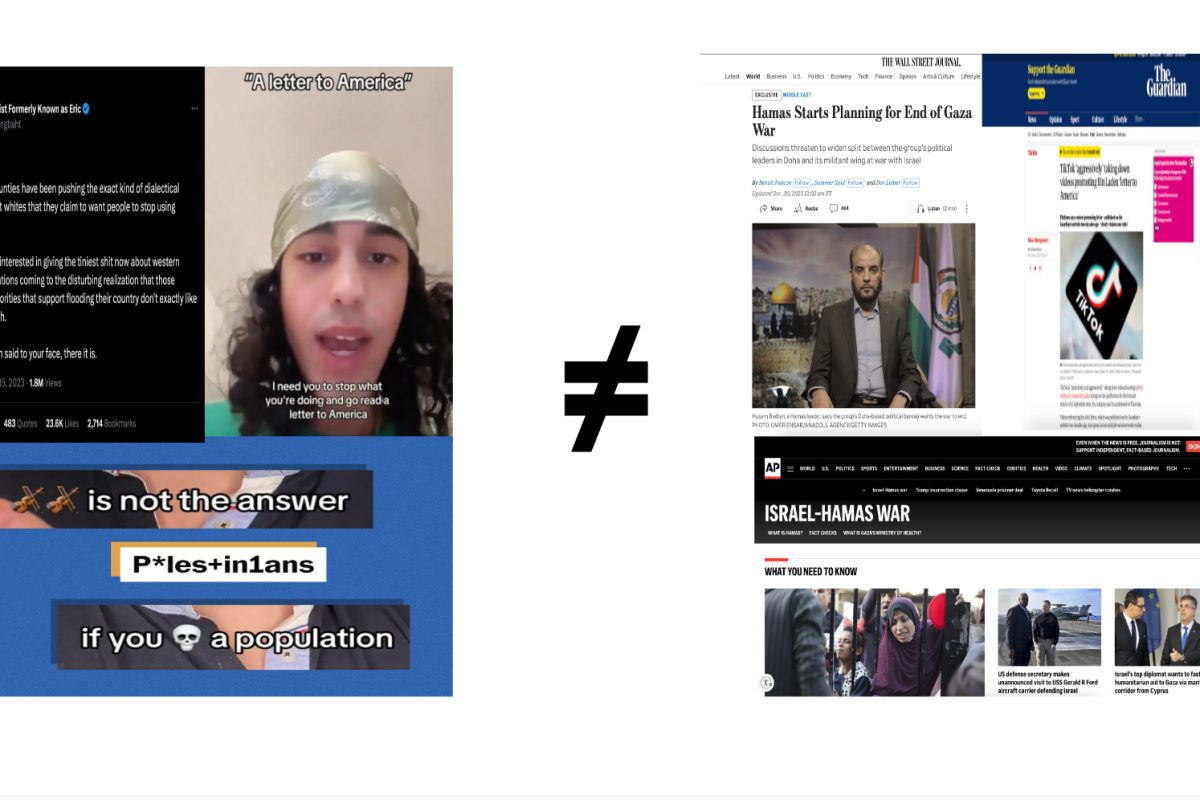

According to New York Times technology reporter Ryan Mac, an X post from Nov. 15 made by “The Artist Formerly Known as Eric” accused “Jewish communities of pushing ‘hatred against whites that they claim to want people to stop using against them.'” This idea aligns with white nationalists’ Great Replacement Theory, which claims that minorities are overtaking and oppressing white populations. In a reply to the post, Musk declared the user saw “the actual truth.” When Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu confronted Musk about X’s antisemitism, Musk laughed and dismissed any malice in his platform’s endorsement of hate speech.

More than anything, Musk’s denial of antisemitism is ironic, considering the very website he owns claims to be “combating abuse motivated by hatred, prejudice or intolerance, particularly abuse that seeks to silence the voices of those who have been historically marginalized.” But content regulations on social media have been at an all-time low when they are needed most.

The probability of being deceived on social media is higher than one might expect: A recent study found that among 3,000 students tasked with identifying if a video was real or fake, only three were correct and researched adequate context. In contrast to social media, The New York Times, The Guardian, NPR and Wall Street Journal are just a few publications that deliver factual, credible summaries of the conflict and demonstrate that authorized publications ought to be prioritized as primary sources of information.

It is not enough for social media organizations to craft a grand mission statement or extensive terms and conditions if none of these promises come to fruition. These policies’ applications must come from people themselves — specifically, content moderators and company leaders behind the screens, who ought to listen to early reports of hate speech as opposed to only caring when the public catches on. If those abusing social media and its freedoms felt the strictness and gravity of policy violation, there would be less appeal to persistently spread malicious opinions or disinformation.

And as for those watching from the sidelines, their trust in social media could finally be restored. If content moderation saw increased follow-through in the form of human, as opposed to robotic, moderation, the prohibition of discriminatory content and faster responses to take-down requests, the regulations people automatically clicked to accept would start meaning something. Users could now realistically believe that within these platforms lies safety, security and boundaries.

I encourage readers to stay off social media, or at least minimize its role as a “news source” for the Israel-Hamas War. The context for this conflict is rich in history and complexity, and simply cannot be diluted with hate speech, or the charged language and fabricated images that often come with social media and are omnipresent signals of misinformation.

No matter what, our capacity to consume information is limited; don’t let the sources you choose be rooted in hate.