As spring bleeds into summer to signal the end of the school year, graduation ceremonies across the country are upon us. While the majority of schools use leadership committees, advisory boards or student votes to elect an inspirational commencement speaker to adequately address the soon-to-be graduates, D’Youville Univeristy of Buffalo, NY, took a more “innovative” approach: Sophia. Not a philanthropist or public figure, but an AI robot donning humanoid features and a DYU hoodie, Sophia was selected by university president Dr. Lorrie Clemo to be a guest speaker to over 2,000 eager students.

Sophia was disappointing.

After student body president John Riazk asked her questions meant to prompt heartfelt, intellectual responses, the Hanson Robotics creation’s answers were described as the “generic” mimesis of “any other commencement address” by New York Times reporter Jesus Jiménez. Even though the school administration had been excited to witness technology that did what was previously thought of as a human responsibility, what happened at D’Youville was an indication that education must continue to put the human experience at the forefront — and not just for commencement speeches.

Chatbots like ChatGPT are dominating the conversation surrounding AI in schools. Not only useful for giving answers to math equations or reciting chemistry equations, ChatGPT recently proved its ability to write entire personal statements used for the college admissions process. Washington Post innovations reporter Pranshu Verma and senior creative technologist Rekha Tenjarla asked a prompt engineer to direct ChatGPT in writing essays from the Common Application and Harvard University. Similar to Sophia’s commencement speech, these AI-generated essays lost their initial shine after being examined by former Ivy League admissions counselor Adam Nguyen.

He concludes that the problem lies not in the fabricated essay’s structure or underlying ideas, but in the smaller details that admissions officers would be keen to observe. Nguyen would have denied ChatGPT a place at Harvard because its “repetitive and predictable” responses “lack supporting evidence” while being filled with “platitudes to explain situations, rather than delving into the emotional experience of the author.” With the college admissions cycle becoming increasingly competitive and stressful on students’ mental health, it can be tempting, and more importantly easy, to resort to AI-generated applications. However, the purpose of the personal statement is to be the one chance where an applicant can “articulate the qualitative aspects of [themself] to the admissions committee and the admissions committee’s major chance to get to know [them] as a person.”

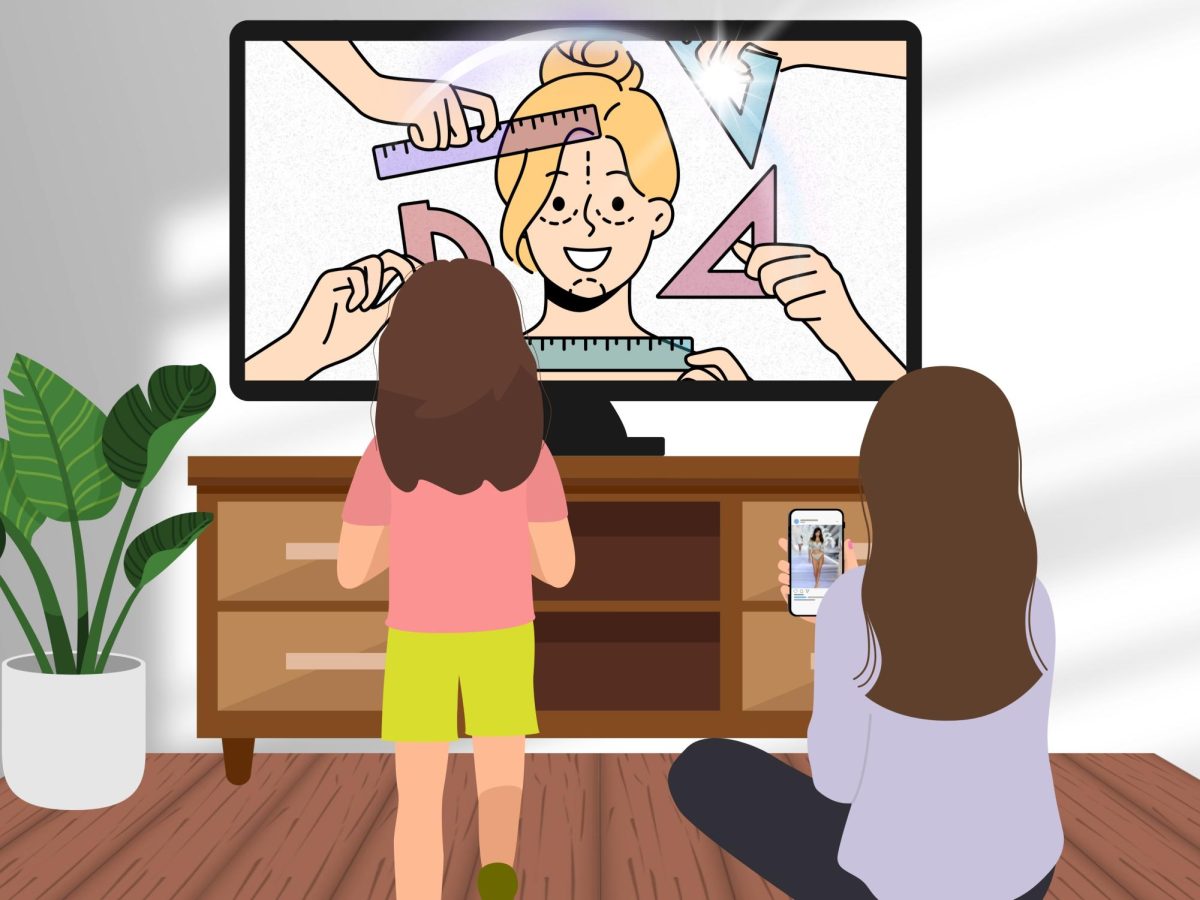

Notice the keyword: person. It is imperative to encourage students to believe their voice is enough and that no technological outcome can compare to their unique lived experience. Imagine if even just 10% of an admitted class exchanged a rare opportunity of self-expression for an AI essay? That educational institution would lose incoming creativity and individuality, both of which are crucial to producing ground-breaking research projects and new cures to diseases. When these students graduate and eventually enter the workforce, their contributions would fall short of those who came before them, as their ideas would not have been rooted in individual integrity, but rather a robot accessible to all.

AI’s growing presence in the field of education is still undeniable. But, we can change the way we frame our relationship with AI from stages as early as elementary school. Sal Khan, for example, has implemented interactive chatbots into Khan Academy, but in a way where the bots are “designed to help students think through problems in math and other subjects — not do their schoolwork for them.”

Education is about equipping students with critical thinking skills and confidence in their own minds, not a laptop and a chatbot. We must not lose focus of student creativity and agency to make way for impersonal technology.