As much as it is a place to understand the past, history class is also a place to process current events. Whether it be election results, climate crises or beyond, more often than not, it is the responsibility of the history teacher to address events of the present.

When students returned to campus following the Oct. 7 attacks on Israel by terrorist organization Hamas, there were initial processing circles offered by Archer’s Jewish Student Union on middle and upper school levels. Additionally, JSU, the Artemis Center and the Service Squad hosted a bake sale in the courtyard Oct. 27, and the proceeds supported humanitarian efforts in Israel and Gaza. They also set up a donation table for the International Committee of the Red Cross during the bake sale.

However, the question of how to address the ongoing crisis — which heavily impacts many members of the Archer community — in the classroom remained, leaving the history department to determine their approach to teaching about it.

Code Red

Following multiple catastrophic events in 2022, including the Uvalde elementary school shooting, history teacher and Director of the Artemis Center Beth Gold decided to take action. In spring 2022, Gold developed Code Red, a crisis protocol that can be employed by faculty members in times of community-wide distress.

“As my role as director of the Artemis Center, oftentimes things fall on me to provide information and resources for people … [to] feel a sense of agency and not like you’re totally out of control,” Gold said. “So with those two hats: [history] teacher and Artemis Center director, I drafted a proposal of Code Red that would be a protocol that we would fall into when there is a crisis, which would include things that would happen in history classes, things that would happen from administration, things that would happen by grade level.”

According to Gold, Code Red seeks to support teachers and students in difficult times. The protocol generally follows an established formula teachers, administration and Deans of Culture, Community and Belonging can follow, but it is adaptable to meet the needs of the community based on the scenario.

History teacher and Service Learning Coordinator Meg Shirk said she appreciates how Code Red gives structure to otherwise daunting topics to cover in classes. She added that it alleviates the pressure of each individual teacher attempting to handle a given crisis and instead acts as a template for teachers to follow.

“I think that as a larger community, there’s so many different avenues that students can get support, and Code Red allows that structure to take shape and to be implemented when things are time sensitive,” Shirk said. “And before that, I just sometimes would feel, as a history teacher, overwhelmed because I think about the students first — how can I meet their needs.”

Supporting Students

History teacher Nicholas Graham said, while efficiently informing students about current crises is important, at the end of the day, the physical, mental and emotional well-being of students takes priority over any lesson.

“If you’ve got family in Israel, or if you’re a person that identifies with this community and you’re fearing for the safety of members of your community, or if you are somebody who was Palestinian [or] Muslim who is now worried about the heightened risk of attacks … me talking about the Balfour Declaration isn’t going to be what your priority is,” Graham said. “Your emotional well-being and physical safety is probably going to be more important at that time.”

History teacher Bethany Neubauer emphasized the importance of creating processing spaces for the community upon the initial unfolding of any crisis — the ongoing one in Israel and Gaza especially. She recognized that not all students may be ready to pick apart facts about a crisis during a class lesson before aptly processing it.

“I think one of the things that we’ve talked a lot about as a community — and certainly in the history department — is often making space first for people just to come together and explore how they’re feeling and think,” Neubauer said. “We’re basically mostly talking about things that are really troubling and sad, and so, until you’ve had some time to process your emotions about it … you might not be ready to be talking about factual information yet. And I think we’ve really learned that that’s an important first step.”

According to Shirk, space is not equal to silence. She emphasized the cruciality of communication during the initial reaction to a crisis and being vocal about the planning that occurs behind-the-scenes.

“I learned an important lesson … that sometimes … people assume that if you don’t hear anything, nothing’s happening. And so a lesson I learned was, just to say, ‘We’re not doing a fundraiser tomorrow, but it’s happening, and we’re working on it,'” Shirk said. “I think just having that message of transparency: we don’t have something that’s happening immediately, but it’s coming, and [knowing] that there’s lots of people working hard on it … can go a long way. So, that was a lesson for me of being really transparent about the planning that’s happening, because if people don’t hear anything they think no one’s doing anything, which isn’t true.”

Classroom Coverage and Conversation

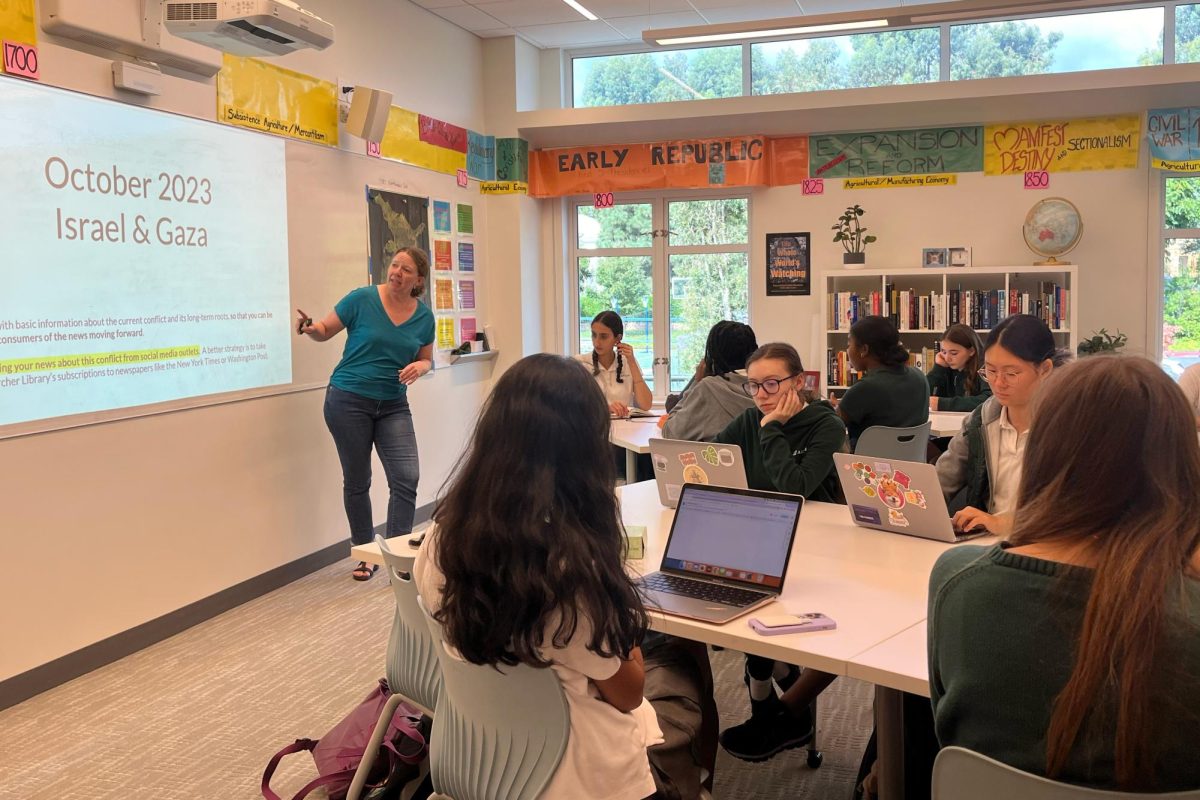

From the life of Marie Antoinette to the Anthracite Coal Strike of 1902, history courses offered at Archer cover a vast array of educational territory. With that same vastness in mind, history teachers curated lessons regarding the ongoing crisis in Israel and Gaza for their students, some of which directly tied into class curriculums.

While each teacher’s approach to teaching about the crisis varies by grade level and course curriculum, there was department-wide consistency in the sense that each class offered context, processing time and discussion space for the ongoing crisis.

Graham said he discussed his approach to teaching about the crisis with other members of the department. Based on their discussion, he said he pinpointed the most important contextual, historical facets of the scenario to educate his students about and based his lesson around that.

“We talked about the things that we thought needed to be emphasized to give students at different grade levels the knowledge and the understanding that they needed to appreciate what was going on and to come to informed judgments and opinions on what was going on as well,” Graham said.

In History Department Chair Elana Goldbaum’s sixth grade history classes, she said she first gathers information from her students, asking them what information they already understand and what questions they may have before discussing the crisis in class. Similarly to Graham, she said her approach may be different with an older group of students, and teaching about crises is based on the age and emotional development of students.

“Checking in with feelings — and that might be verbal, it could be written — and everyone’s a little bit different. Some people are quieter and would like to journal. Some people have different bandwidths for how long we want to talk,” Goldbaum said. “One thing we did the other day was talk about how do we know when we’ve had too much information. So we talked about what does the body feel like when you’re starting to feel overwhelmed and you’re ready to shut down? And then what do you do to take a break? We are inundated by news … and I share that with my students, too.”

Additionally, Goldbaum said, more generally speaking, prioritizing which crises receive in-class coverage is an ever-evolving, painful experience, but the ones that have the most relevant impact on the community must come first in the classroom.

“I do want to emphasize that … the war in Ethiopia, the displacement of the Armenians, the ongoing fight for women’s rights in Iran: we have no shortage of international tragedy, and it can feel really painful to prioritize one over another. But at the end of the day, we think about what is impacting our Archer community first,” Goldbaum said. “But I want to encourage all students to stay informed because there’s so many causes out there, and I think our world is a little bit better when we’re more informed.”

Human Versus Teacher

Despite an increasing usage of artificial intelligence in lesson plans and homework in other schools across the nation, one fact holds true: teachers are not robots. According to Shirk, it is imperative to be cognizant of the complex, human emotions teachers possess, despite being main sources of information for students in times of crisis.

“Sometimes, I think students forget the teachers are people first,” Shirk said. “And so [teachers are] managing their own emotions and want to show up in the right way for students to navigate these really tricky topics.”

Neubauer said, while she understands the importance of being a stable role model for students in times of deep tragedy and crisis, she also finds importance in communicating her own emotions to students. She emphasized that being a responsible adult can go hand-in-hand with maturely and professionally sharing one’s emotions — a practice which she said is especially important when discussing distressing topics in class.

“I do tell my students how I’m feeling and acknowledging that partly as a way to let them know that it’s upsetting for me, too, and to model that it’s important to say when you’re just feeling really overwhelmed and sad. [If] that’s a reaction that they’re having, that is okay,” Neubauer said. “I really do think, obviously, as the adults, it is our responsibility to take the lead, but also to show that we’re as human as everybody else.”