Food and the self: Changing attitudes towards eating disorders

Teenagers fear the stigma of being overweight, yet this pressure can lead to eating disorders, which have their own stigma. Archer’s human development program is trying to fix this pressure and teach students how they can overcome this.

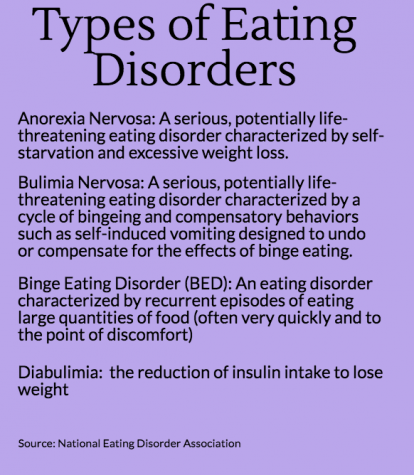

According to the National Association of Anorexia Nervosa and Associated Disorders, “at least 30 million people of all ages and genders suffer from an eating disorder in the United States.”

“Eating disorders involve self-critical, negative thoughts and feelings about body weight and food, and eating habits that disrupt normal body function and daily activities,” according to KidsHealth.

“Eating disorders involve self-critical, negative thoughts and feelings about body weight and food, and eating habits that disrupt normal body function and daily activities,” according to KidsHealth.

Archer Fitness and Wellness teacher Alison Hirshan commented on the idea that they are also a form of mental illness.

“Eating disorders are a mental disorder or mental issue. It is very correlated with mental health. It is paired with anxiety and depression. The onset of [an eating disorder], with college, for example, [is common, since] it is such a big change in your life. It can be a traumatic event or a huge life change that is basically out of your control,” she said.

Living with an Eating Disorder

Archer senior Vanessa* developed her eating disorder at the end of her eighth-grade year when she started feeling a lack of control due to her parents’ fighting and the stress of doing well in school.

The one thing she did have control over, however, was food. She noted that she abandoned the foods she once loved and performed a “happy dance” each time she weighed herself. She started to eat less and less.

“It started with me deciding to go on a diet,” she said. “When I started, I thought it was certain foods that would make me skinny — so when I cut those out, I started cutting out more and more, and counting calories and just going down that path from there.”

“Food consumed my mind,” she said.

When people started to recognize her weight loss, she said that the comments “felt satisfying.”

People told her things such as, “You honestly have the perfect body.” Such a tiny waist!” “Skinny mini!” or “Wow! Thigh gap goals.” However, as time passed, the compliments were turning into concerns: “You literally lost thirty pounds” or “Oh my gosh, I can totally see your spine.”

When a close friend brought her decline in weight to her attention, she did what most people would do: deny it. However, when her mother approached her “with concerns about loss of menstruation and a steep decline in weight,” Vanessa realized that she had to face this reality.

“Part of me felt a little relieved that my mom approached me,” she said. “I remember sitting on my bed and I just started crying. She told me that [she] and my dad were going to do anything they could to make sure I would be better.”

Vanessa was diagnosed with an eating disorder. She began to see a nutritionist and a therapist.

“I was also diagnosed with general anxiety disorder,” she added. “It’s always a question of which came first— whenever I feel anxious or overwhelmed I think about food, but then when I think about food I become anxious.”

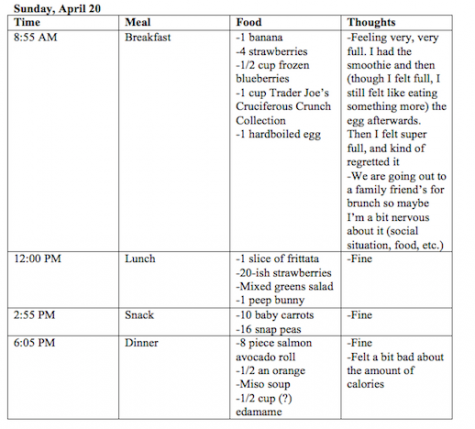

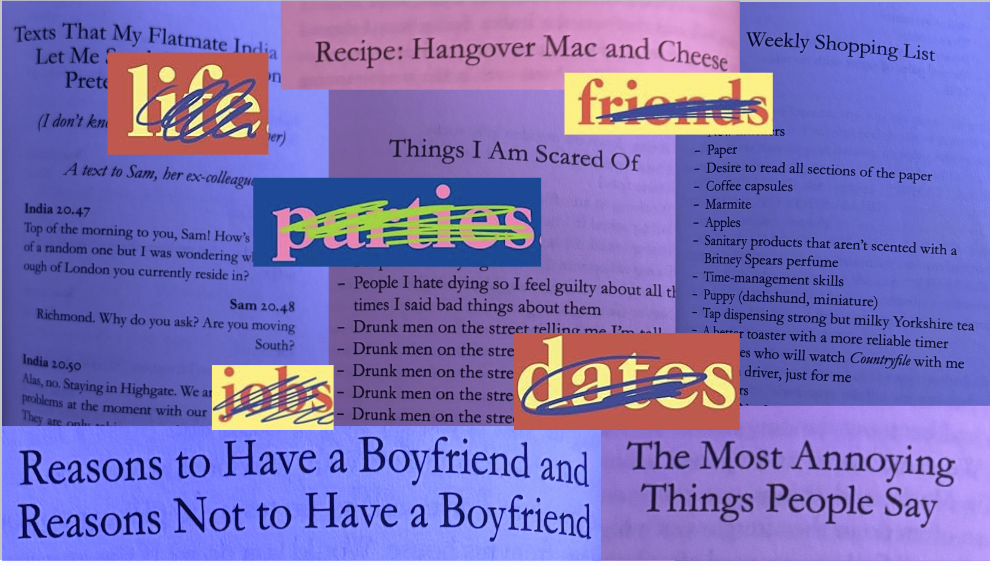

An example of one of Vanessa’s food diaries. She included the time, what type of meal it was, what she ate and how she felt after each meal.

Her diet had become a math equation. She recalled that she used to have powdered peanut butter that contained 40 calories per two tablespoons to avoid the 200 calories in normal peanut butter.

Her nutritionist first had her increase the amount of powdered peanut butter she had, before switching her to normal peanut butter. She had to start slow and build up the intake.

To help her become aware of what she was eating, her nutritionist had her keep a food diary to log her intake and emotions about food.

“With my therapist, I had little challenges per week. So, one of them would be like eat dessert with friends — and doing it with friends would get my mind off of the food,” she said.

“There were certain times I didn’t hang out with friends or changed plans because of the food, so part of it was making food more comfortable socially.”

Even though she is in recovery, and has been since her freshman year, it has not been easy, she said.

Vanessa remembers having HD units on nutrition and recalls a time when a psychologist came to Archer to talk about eating disorders, but the psychologist never had an eating disorder. She said education about eating disorder focused on a friend, or “other people.”

“I feel like the reality that I or anyone else in the grade could have an eating disorder ourselves wasn’t really addressed,” she said, “so I wish there was some programming not just around how to help friends, but how to help yourself or seek help.”

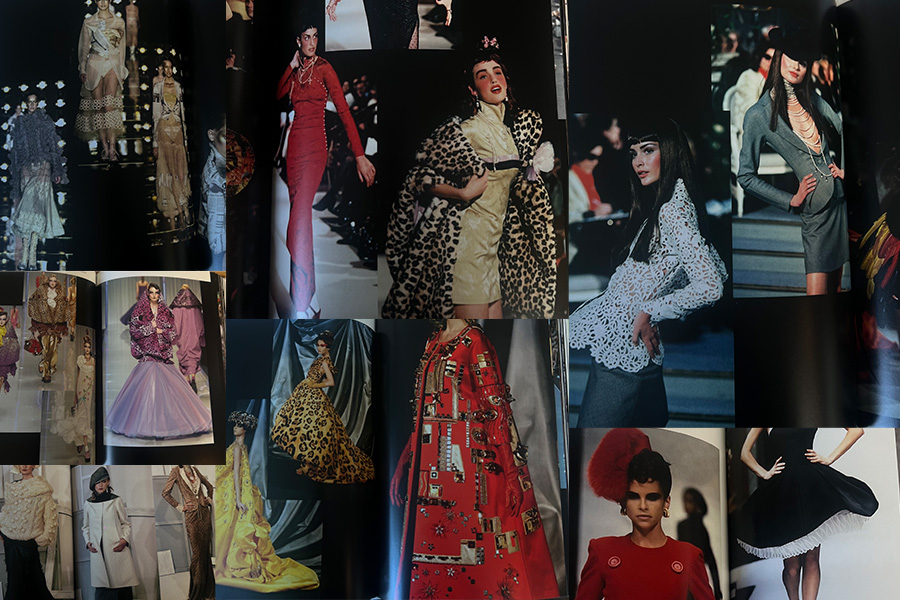

In an email interview, Hirshan commented on how the HD program has changed since Vanessa was in HD. Students are now watching documentaries, analyzing diversity in magazines and using online resources to create a personal toolbox to support body confidence and self-love.

Additionally, she said, this year they brought in a guest speaker from The Renfrew Center Eating Disorder Treatment Facility to talk about eating disorders and where they stem from and how you can help a friend.

“Our goal is to bring awareness and that we encourage students to seek help from our counselor, Ms. Lancaster, if they have any questions about themselves or friends,” Hirshan wrote. “I also encourage parents to help normalize these topics by creating a safe and supportive dialogue at home.”

“If someone does develop an eating disorder,” Lancaster said, “be supportive just as we would be with anyone having a hard time.

Assumptions about Weight Loss

Weight loss due to physical medical problems often leads to assumptions.

During her junior year, Alyssa Downer ’17 suffered from a stomach illness that prevented her from being able to eat.

“I was unable to hold any food down and had eventually lost my appetite altogether,” she said.

Downer was confronted by friends and family, just like Vanessa, asking about her eating habits, where all of her body weight had gone and what she was doing to herself.

I was angered by the fact that because they had thought I had an eating disorder, they decided that I didn’t need medical attention. That I would be OK, and should go see a therapist maybe.

— Alyssa Downer

“I had been told by people that I should just ‘eat more’ and that’ll fix my problems,” she said. “I had visited doctor after doctor to find a solution, but 90 percent of the doctors I had visited had told me that I was anorexic or bulimic. I [was] frustrated because I felt that the doctors were choosing the easy way out.”

As Downer saw more and more doctors, she grew even more irritated because they weren’t acknowledging her condition.

In the end of her journey, she was diagnosed with Median Arcuate Ligament Syndrome — a problem with compression of the arteries above your stomach.

During this time, Downer believed that she was “better than to be diagnosed with an eating disorder.” Looking back, she said she is “ashamed” of this belief.

Downer realized that she used to assume that people chose to starve themselves, but she understands now that it is a serious medical condition.

Finding Empathy

School counselor Patty Lancaster said it’s not unusual for people to feel superior to those with eating disorders, and this misconception can delay treatment.

“I don’t think that anybody would choose the difficulty and the heartbreak that goes along with having an eating disorder, and I think that that’s the misconception — that it’s a choice or a diet gone wrong,” she wrote in an email interview. “What is important to know is the sooner someone can get help, the better chances of recovery. This is difficult because there is so much shame and denial around it, thinking it can be controlled or having distorted body image.”

Even though Downer did not have an eating disorder, she said now she “empathizes with the girls — with everyone — who suffers from such a disease.”

Downer credits Archer’s Human Development class lesson on eating disorders with her change in heart. Before the lesson, she “thought lightly of eating disorders; that people should just choose to eat normally, to just live healthfully.” After the class, she realized “that’s not the case.”

If someone does develop an eating disorder, be supportive just as we would be with anyone having a hard time.

— Patty Lancaster

Hirshan, who currently teaches HD, believes that the conversation should move from body image to self-image.

“We introduced the concept of ‘normalized eating,'” she said. “The basic concept is that during the day you are eating to fuel your body. Therefore, rather than the bag of chips, you can have the apple to fuel your body. But, if you feel like it, treat yourself. We don’t want to instill in them that you have to eat healthy all the time, and we don’t want them to feel guilty or shameful. It is hard to find that balance, but we have to teach them what’s helpful but to also eat what they want.”

Downer wishes that there was more education in schools and the community to make people more aware of eating disorders and other diseases.

“I know what it feels like to feel helpless in your own skin. To feel like you want to get better, but don’t know how. To feel that ‘too skinny’ is not good enough,” she said. “To the people with eating disorders, I know you are struggling, and I know it is not your fault.”

*Name has been changed by the request of the source due to privacy concerns.

Anika Bhavnani became a member of the Oracle staff in 2015. She was promoted to co-Voices editor in 2016 and was promoted to editor-in-chief for the 2016-2017...

Sonia Arora • May 15, 2017 at 1:56 pm

Wonderful work, Anika! You handled a tough topic with sensitivity and respect.

Best wishes,

Ms. Arora

Alison Hirshan • May 12, 2017 at 4:42 pm

So happy I was able to add some insight! Extremely well-done article, so informative, and SO important for your peers to read!

Harley Smith • May 12, 2017 at 11:21 am

Amazing article Anika!! Thank you for shedding light on such an important topic!

Syd Stone • May 12, 2017 at 11:16 am

This is such an important article and I’m so proud of you for taking it on!

Alyssa Downer • May 12, 2017 at 1:49 am

Such an important read and a beautifully written article!

Anna Brodsky • May 11, 2017 at 10:07 pm

Anika, thank you for telling this story! The piece was incredibly well written, and you dealt with difficult topics with grace and integrity 🙂

Nelly Rouzroch • May 11, 2017 at 8:12 pm

Amazing article Anika!

Alexandra Chang • May 11, 2017 at 7:17 pm

This is such a fantastic article, Anika. Thank you for shedding light on such an important and relevant topic <3

Cybele Zhang • May 11, 2017 at 6:45 pm

Great article, Anika! Thank you for calling attention to such an important issue.

Ms. Terry • May 11, 2017 at 5:55 pm

FANTASTIC article Anika!! Thank you for sharing this with our community, and please thank your anonymous source for sharing her very personal struggle with all of us. Her experience will undoubtedly help another young woman who is fighting for balance in her own life.

In my former professional life, I knew MANY young women with eating disorders and/or body dysmorphic disorders with varying degrees of severity.

Educating young women on this topic is so incredibly important, and I feel you have done this community a great public service with your article.

#gratitude

Ms. Terry

Ms. Webster • May 11, 2017 at 3:31 pm

Such an illuminating and important read! Thank you, Anika!