‘It’s a 21st century learning skill’: Media literacy education ‘critical’

Photo credit: Emma London

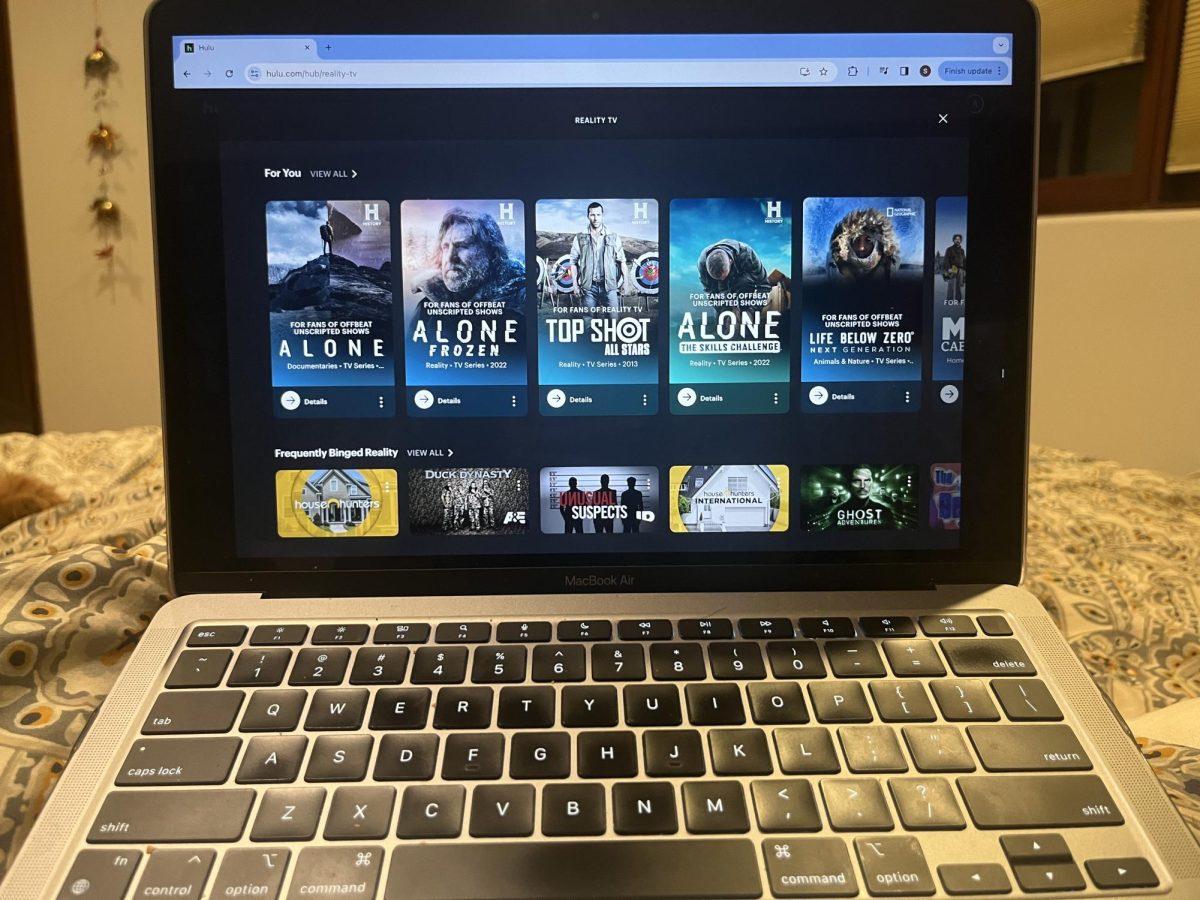

Sophomore Isa Ionazzi does research for a project in history class. A study published in 2017 by the Stanford Graduate School of Education found that 80% of the students tested couldn’t identify biased content from mainstream media.

Headlines like, “Spanish man builds 60-foot spaceship to visit planet from his novels,” “President Obama Bans the Pledge of Allegiance From Schools” and “Miami-Dade to Create Freeway ‘Texting Lane’ to Accommodate Millennial Drivers” continue to surface on popular news sources.

Only one of these headlines is true, but how can media consumers tell?

With the rise of “fake news,” media consumers struggle to decipher what is true and false on the internet. According to a poll by Common Sense Media, 48% of kids say that they value following the news, but it can be unclear what articles are real or fake.

Sophomore Ava Thompson looks through books in the library.”[Students must be] sure that they’re finding multiple different sources so that they’re able to compare different perspectives,” faculty advisor for UCLA’s Teacher Education Program and media literacy expert Jeff Share said in a phone interview.

“I think, in general, it would be a mistake that just because they’re younger that they don’t have the ability to think critically,” faculty advisor for UCLA’s Teacher Education Program and media literacy expert Jeff Share said in a phone interview. “It’s very seldom that [students] get any kind of media literacy class. It’s a really big problem when people just use their old ideas of information or research and not recognize that it’s very different now.”

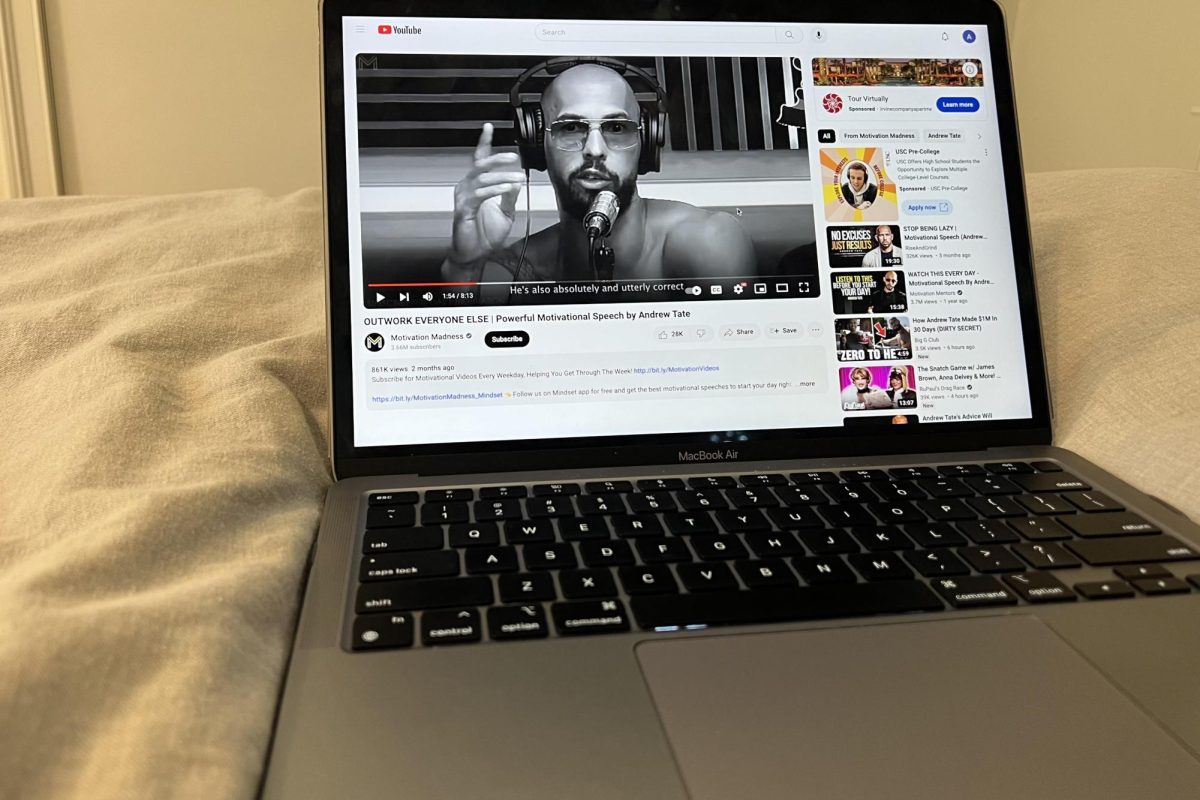

A Stanford study found that 80% of students believed that sponsored content was a real news story, partially because many students are not educated on what sponsored content means. Share explained how the primary goal of media companies is to make a profit, not to protect consumers. In 2016, Google made $79.4 billion in ad revenue.

“We go on Google or Amazon and we do our searches and we think, ‘Oh wow, this is great. I got my information for free.’ It doesn’t really work that way,” Share said. “Everything you do, [media companies are] capturing and selling to somebody else. You are being used in ways that most people just have no awareness of.”

According to Share, media literacy is the skill of consuming and creating all types of media, from books to Buzzfeed articles. A common misconception about media literacy is that it only involves being able to take in different kinds of media, but a key component of being media literate is being able to produce media yourself. As the world becomes increasingly diverse and interconnected, the concept of media literacy has changed as well.

“So much has changed so fast that a lot of people just aren’t even realizing what major shifts there’s been,” Share said. “Just last year, for the first time ever…over half the world’s population is online.”

Sophomore Hannah Joe said she utilized her media literacy education when doing research for a history paper.

“I had to get a lot better at identifying credible sources,” Joe said. “I originally had planned to use a source that I found out wasn’t really credible by comparing it to the rest of the information I found.”

In 2017, the Pew Research Center found that two-thirds of adults in the United States get their news from varying social media platforms. A study conducted at Stanford that tracked engagement with fake news on Twitter found that fake news sites on Facebook had approximately the same amount of engagement as credible media outlets.

“I don’t think there’s ever been a time where it’s been more critical to be an analytical thinker when it comes to the media because so much of what’s getting put out is either fake, inaccurate or has immense bias,” history teacher Margaret Shirk said. “A lot of media outlets are trying to trick us.”

The Fake News Media is going Crazy! They are suffering a major “breakdown,” have ZERO credibility or respect, & must be thinking about going legit. I have learned to live with Fake News, which has never been more corrupt than it is right now. Someday, I will tell you the secret!

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) March 28, 2019

Fake news has always existed, but the concept came into the spotlight during the 2016 elections when President Donald Trump was elected. In 2017, Trump mentioned fake news in his tweets 73 times; he accused the New York Times, Washington Post and CNN, among other prominent news sources, of publishing fake news.

Penn State University defines fake news as “sources that intentionally fabricate information, disseminate deceptive content, or grossly distort actual news reports.” Indicators of fake news are often satire, bias and clickbait. Social media platforms such as Facebook have begun to change their algorithms to limit exposure to fake content.

In a survey sent to all high school students with 46 responses, 91.3% of students responded that fake news makes it harder to do research online, but 57% of students use sources even if they know the information is not entirely credible.

“It’s getting harder to spot [fake news] because they’re so thoughtful in how they craft the images, the headlines and the URLs,” Shirk said. “You have to be such a detective to figure out what’s real and what’s not.”

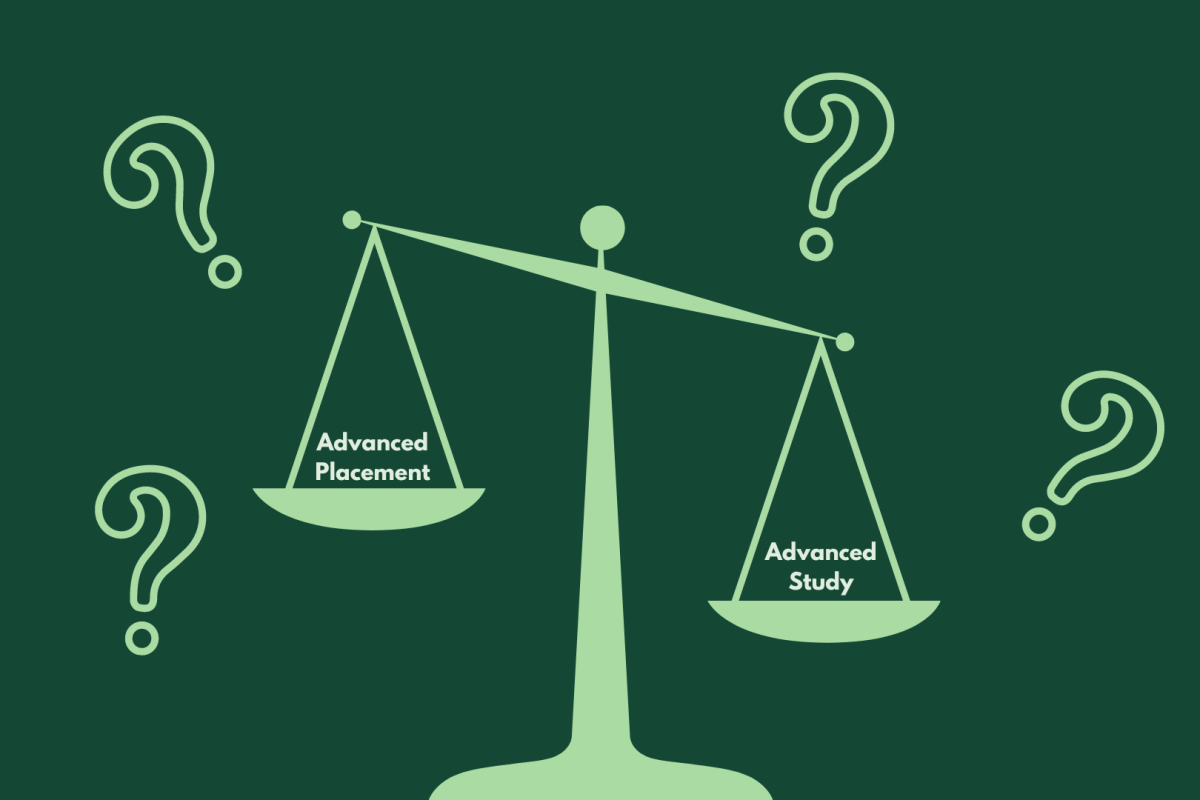

A Common Sense Media study found that 31% of kids who shared a news story in the span of six months later found that the story was inaccurate. Studies show that media literacy education is the best way to ensure people can distinguish fact from fiction online. At Archer, media literacy education is incorporated into English and history classes in eighth and ninth grade.

“Because it’s a 21st-century learning skill, teachers are being more mindful with explicitly teaching it so that when you go out into the real world you’re able to consume media, question the media and sift through all of the information that’s coming at you every day,” Shirk said.

Sophomore Isa Ionazzi said she “value[s]” Archer’s media literacy education.

“Archer taught me media literacy,” Ionazzi said. “If I hadn’t come to Archer I probably wouldn’t know what sources were reliable and I’d be using information that was incorrect.”

According to Share, red flags for an inaccurate source include bad language, extreme adjectives or hyperbole. Students need to be “cautious” to find accurate articles.

“My big lesson is that it’s much more complicated than people think, and it means that we need to take a more active role when we’re trying to find out any type of information,” Share said. “It’s really important to recognize that nobody is ever completely objective. All journalists, all information, needs to be questioned about its bias, its construction and its trace of what they tell or what they don’t tell.”

Emma London joined the Oracle as a correspondent in 2017 and as a staff writer in 2018. She is on Archer's equestrian team and plays the viola in upper...