Op-Ed: The Oscars (for once) didn’t disappoint

Photo credit: Amanda Greene

The Academy Awards, and the gold Oscar statue which punctuates them, have long been a symbol of cinematic excellence. However, the Academy has been criticized for snubbing female creators, and creators of color. In a yearly awards show renowned for being awkward and disappointing, the 2020 Oscars surprised me.

When I flipped to ABC at 5 p.m. Sunday night, I expected to be disappointed. I braced myself of another year of overpriced glitzy dresses, awkward teleprompter one-liners and makeup artists and costume designers struggling to finish their speeches before being played off stage. Most of all, I was ready for another year which championed filmmaking by and for the white man. But this year’s Oscars had a surprising Hollywood ending: they proved me wrong.

The Academy seemed to set the stage for another disappointing year, with Cynthia Erivo as the only black nominee in a major category, no women nominated for best director and most of the best picture nominees focusing around white narratives. However, many of the Oscars attendees did not take this lightly. Academy Award winner Natalie Portman donned a black cape with the last names of snubbed female directors embroidered in gold. Big names like Brad Pitt, Saoirse Ronan and Keanu Reeves brought their moms to the Oscars and posed with them on the red carpet. Although this choice seems small, I believe it is a powerful statement for actors with frequently covered romantic lives to champion familial love and admiration of influential women in their lives instead of tabloid culture.

To begin the Oscars, Janelle Monae, a black and queer artist, performed an energetic number. Accompanying her were dancers dressed in costumes referencing films that were disappointingly not nominated, including several with primarily black casts, such as “Dolemite is my Name,” “Us” and “Queen and Slim.”

In the middle of the performance, Monae celebrated female directors and wished the audience a happy Black History Month. She sang a version of her 2010 hit “Come Alive,” with lyrics reworked for the Oscars. Referencing South Korean Bong Joon-Ho’s best picture nominee, Monae sang “Parasite, it’s time to shine, it’s time to come alive, ’cos the Oscars, it’s so white.”

Although these moments were entertaining and heartfelt, the night still felt like any other Oscar event. It was not until the best director category that I began to feel like Hollywood might be changing.

In what many media outlets are calling an “upset,” South Korean director Bong Joon-Ho won the Oscar for his directing in “Parasite.” It was beautiful and compelling to see a relative outsider to Hollywood win an accolade usually reserved for Academy royalty such as Martin Scorsese and Quentin Tarantino, who were both nominated against Bong this year. It was also incredible to see Bong, who has essentially earned the place of most powerful director, speak in his native, non-Western language and seem comfortable and welcome on the Dolby Theater stage.

The Academy itself also embraced cultural relativism, renaming the Best Foreign Film category “Best International Feature Film.” This language disparages the idea of subtitled or culturally different movies as “other.” The word “feature” makes these films seem just as important and relevant as any American or Western movie. When Parasite won the award this year, director Bong said he “supported” this change. He too saw it as a sign that Hollywood was changing.

Taika Waititi also made history at this year’s academy awards, taking home the award for Best Adapted Screenplay for Jojo Rabbit and becoming the first person of Maori descent to win an Oscar.

“I dedicate this award to all the indigenous kids around the world who want to do art,” Waititi said. “We are the original storytellers, and we can make it here.”

Later in the night, Waititi gave the Academy’s first land acknowledgment, recognizing that Los Angeles is the ancestral land of tribes native to California.

“Tonight, we have gathered on the ancestral lands of the Tongva, the Tataviam, and the Chumash,” Waititi said. “We acknowledge them as the first peoples of this land on which the motion pictures community lives and works.”

This sentiment was refreshing, and opened my eyes (as well as those of many living or working in Hollywood) to the invisibility of Native Americans in much of the film industry and in our city despite the fact that the land we live in was their home long before ours.

The land acknowledgment came as a welcome surprise, but few of the actual Oscar winners were quite so much of a shock. In fact, I was so confident that Joaquin Phoenix would win Best Actor for his role in “Joker,” that I spent more time wondering how he would use his 45 seconds than whether or not he would win. Throughout awards season, Phoenix has been using his awards speeches to critique Hollywood’s attitude on the environment and racism. There was no question he had something up his sleeve for the Oscars. However, he did so much more than use his platform for a single issue. While some of his speech focused on animal rights, something often ignored throughout Hollywood and the mainstream media, he also encouraged other celebrities to use their platforms similarly.

Phoenix also included poignant references to his past. “I’ve been cruel at times, hard to work with, and I’m grateful that so many of you in this room have given me a second chance,” Phoenix said. “I think that’s when we’re at our best — when we support each other…That is the best of humanity.”

After this, Phoenix choked up while giving a testament to his late brother, River. He concluded his speech with a lyric his brother had written at 17 years old: “Run into the rescue with love, and peace will follow.”

I think at times we feel or are made to feel that we champion different causes. But for me, I see commonality. I think, whether we’re talking about gender inequality or racism or queer rights or indigenous rights or animal rights, we’re talking about the fight against injustice.

— Joaquin Phoenix, 2020 Best Actor Acceptance Speech

Just when I thought the night couldn’t get any more emotional, Jane Fonda announced best picture. My family sat on the edge of our seats, holding out hope for a special end to a unique night. I had (somewhat bitterly) accepted that Parasite was probably unlikely to win Best Picture, especially since it had already won three other awards that night. Although I believed it fully deserved Best Director and Best International Film, I figured there was too much competition at the awards and too little openness in the academy for it to go any farther.

When Fonda announced Parasite as Best Picture, my mom and I screamed and jumped from our seats. Bong Joon-Ho, along with producer Kwak Sin-ae and most of the film’s cast beamed as they mounted the Oscars stage. As the small golden statue exchanged hands, all of my cynicism and indifference towards the Oscars shattered for a moment. I felt like the wall separating me and my fellow Asians from the rest of Hollywood, had, at least for the night, crumbled.

Hearing Bong and other members of the production team speak their native language (with the help of an interpreter) made me think back to my classmates in elementary school, who, imitating eastern Asians, would pull up their eyes up to make them narrow and speak gibberish. Perhaps children today will see Korean as a language of success and power rather than something trivial and funny. I saw all of the beautiful actors and actresses smiling on the stage and thought about, although none of them were nominated, how Asian features may finally be seen as attractive and worthy of admiration and even envy instead of parody.

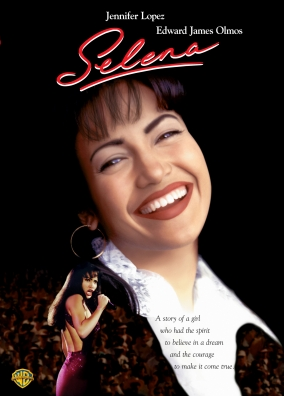

The Oscars certainly have a long way to go to reflect the vibrant diversity of Los Angeles and the film industry. Conversations on how to categorize nonbinary nominees or the lack of Latinx creators felt swept under the rug. But for the first time in years, I feel like there was a chance that these conversations will be acknowledged in the near future. If the Academy Awards are to become relevant again, they need to promote the kind of unbridled frustration and triumph I saw in Hollywood last Sunday night.

The 2020 Oscars were far from perfect, but they reminded me of the magic of film to unite us.

Rio Hundley was involved in the Oracle from 2017-2021. She graduated in 2021. She was promoted to Sports Editor in 2019 and became Features Editor in 2020....

Natalie Kang • Feb 24, 2020 at 11:46 am

Beautifully written! Thank you for highlighting such an important and inspiring accomplishment in film.