Commentary: My ongoing relationship with comparison

Photo credit: Maia Alvarez

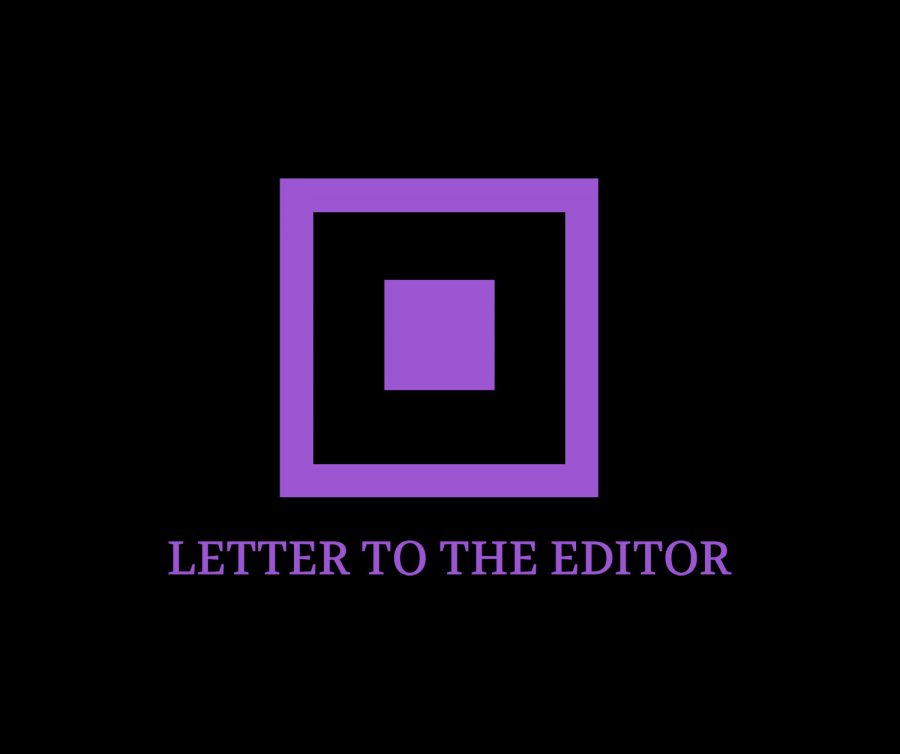

My speech and debate teammates lift me up for a photo. Even if I do not perform my best at a tournament, I never feel the need to compare myself to other competitors. My enjoyment of the activity is my primary focus.

February 12, 2023

What I remember most from elementary school are the tests I took. It was not their content that shaped me but, rather, the way I received them. Instead of handing out assessments as soon as they were graded, my teacher announced our scores aloud. She began by telling the class who received a perfect score and kept listing names and numbers until we knew who did the worst.

Sometimes, we laughed. Most times, we remained silent. Every time, I felt a mix of emotions.

On one hand, I felt accomplished knowing who I scored higher than. On the other, I felt inferior to those I scored lower than. No matter what, my conflicting feelings always compounded my desire to work the hardest, to be the best. By the time I finished the fifth grade, my sense of self-worth was rooted in how my academic performance compared to that of my peers.

I was 10 years old.

After four-and-a-half years at Archer, my continued desire to compare myself confuses me. With the school’s encouragement of a growth mindset and keeping grades confidential, I should be self-fulfilled. But although I am surrounded by socioemotional support, I am also surrounded by a myriad of accomplished classmates.

My friends are talented musicians who have played at international music festivals, mathematicians who take college-level courses for fun and dancers who have brought home awards from regional competitions. They swim, tutor, engineer robots, play the piano and look after their siblings. When they complain about an A- or call themselves “lazy,” it is easy to question my work ethic. It is even easier to question my worth.

I have trained myself to outrun comparison by feeding into it. More often than not, my motivation to embark on an extracurricular or enroll in a class was because my friend tried it first. I have thought doing things I had no interest in would make me similar to those who inspired me.

This pattern persisted throughout middle school and only heightened with remote learning. Tiredness turned into fatigue, which turned into exhaustion, which turned into burnout.

What I learned is this: dedication, without passion, takes a toll.

However, no matter what aspect of myself I decided to deem as worse than my peers on a given day, one thing remained untouchable: speech and debate. After first discovering the team during a Zoom practicum session, I was deeply enthusiastic about it — even in a remote setting. Its ability to combine my interests in public speaking, theater, politics and writing hooked me and gave me hope that I could find the excitement and drive I had lost from chasing after unfulfilling dreams.

As I walked into the first practice during my first week of ninth grade, I watched team veterans deliver speeches about complex issues with unparalleled eloquence. My eyes glazed over their computer screens that showed intricate cases made to debate legislation. I knew stepping into this intimidating environment would put my initial interest to the test.

When the season officially began, I immediately realized I was not gifted with an abundance of natural talent. Within my first year on the team, my attempts at drafting a Declamation, Humorous Interpretation and Informative speech failed. My teammates had complete drafts of their speeches within three weeks. Furthermore, they beat me at competitions and qualified for tournaments I was not yet skilled enough for.

Though I was met with numerous opportunities to be disappointed in myself for doing worse than others, any initial sadness did not last long and was always overpowered by a compelling desire to try again. Even though a tournament might have brought me low rankings and losses, I could barely focus on my defeats or my opponents’ triumphs. All I wanted to do was recreate the perfect flow I found when presenting in front of an audience and sense once more the adrenaline coursing through my veins as my rounds began.

This happiness was mine and mine alone. For the first time, self-fulfillment came easily.

Speech and debate broke my habit of comparison. It allowed me to ask myself: “Why should I compare when not doing so feels better?”

My point is not that speech and debate is the universal cure for comparison. But finding a niche activity or passion that you genuinely love can be an answer — an answer to critical thoughts, ideas about supposed inferiority to those around you or an empty feeling of not being “enough.”

There are still times when I compare and weigh my achievements against those of my peers. I have accepted comparison’s presence in my life but have diminished it as well.

Being content with my own journey — whether that is academic, extracurricular or personal — is freeing. It is incomparable. So are you.

Ms. Chakravarty • Feb 15, 2023 at 5:34 pm

Thanks for sharing a thought-provoking read, Allie!

Siena Ferraro • Feb 14, 2023 at 9:28 pm

Allie! To say I’m proud of you would be a major understatement. You’ve crafted this piece with such refined skill and have given light to a topic so many of us waive off as “normal.” Thank you for being an absolute gem of a journalist. So proud of u!

Lucy Williams • Feb 12, 2023 at 12:58 pm

Allie, you are incredible. The articulate nature of this piece perfectly showcases your incredible story with the perfect Allie insights. I’m so proud of this!!