Op-Ed: Stop worrying about AI art

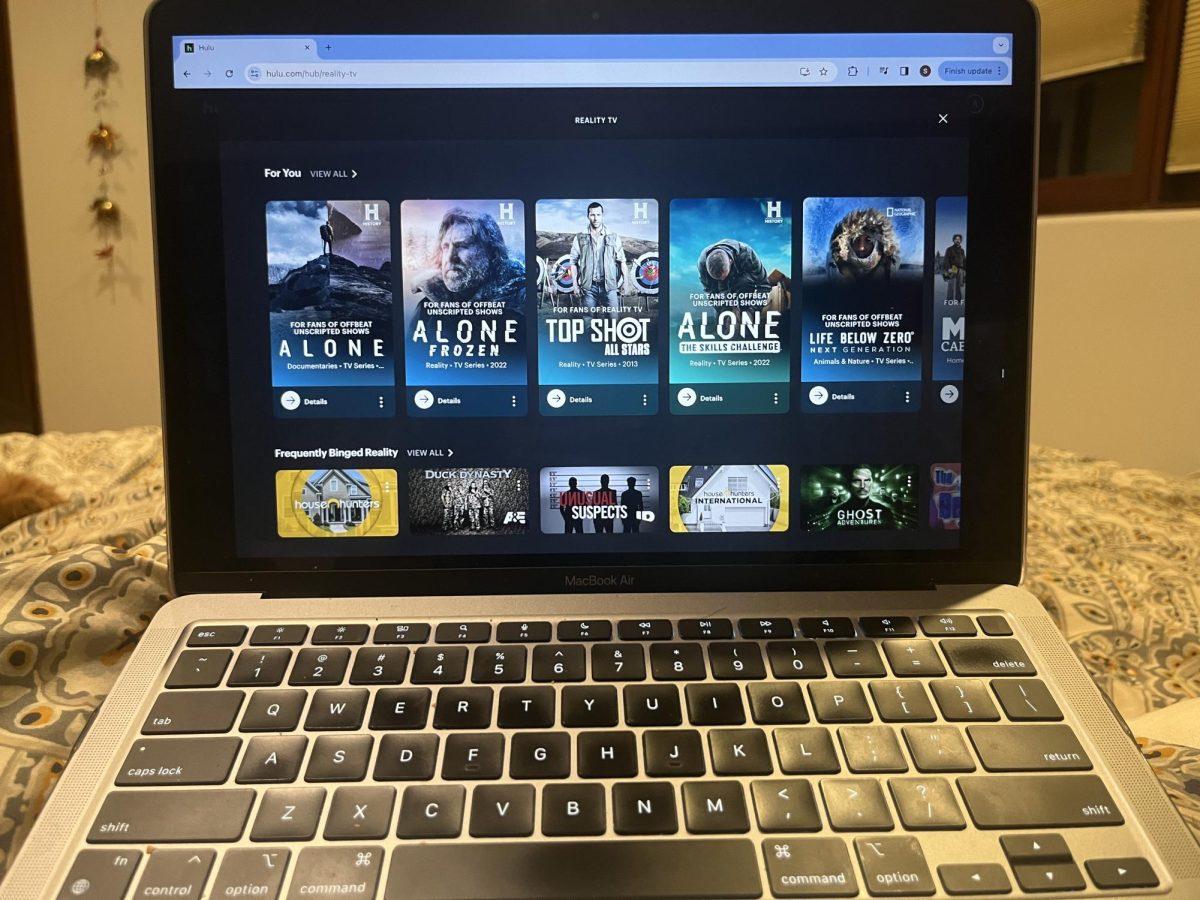

Photo credit: Allie Yang

The artificial intelligence program, Lensa AI, generates a digital portrait of Lily Poon (’25). With the rise of AI-generated art, artists fear for the security of their jobs. Image by Lensa AI prompt by Anthony Poon.

May 6, 2023

How does it look so realistic? How is it this detailed? How is this possible?

These were questions I asked myself when viewing AI-generated art for the first time. The piece was a portrait of my friend with fairy-esque features like a crown made of flowers and wings. Though the portrait had a mythical feeling, it still captured her appearance accurately.

This image technology is not a pioneer. AI art has been present since 1973 when computer scientist Harold Cohen developed AARON, the first artificial intelligence program that could turn code into drawings. While the first works were purely abstract, the possibilities have evolved. Now, programs like DALL-E2, Midjourney and Stable Diffusion let users input hyper-specific prompts to get an award-winning product in seconds.

The popularization of AI art has come with criticism, particularly from artists who fear for their jobs. However, the idea that humanity cannot adapt to this development is fundamentally flawed. AI art does not signify the art world’s shift to dystopia.

The rise of new technology and subsequent backlash is centuries old. For example, photography was deemed art’s competitor by 19th-century art critic Charles Baudelaire. Yet, the camera has not defeated the artist. Rather, the two coexist in a consumerist society that welcomes all forms of creation. Centuries later, photographers faced the same dilemma when the first photo-taking smartphone was released in 2000. However, the smartphone’s birth was not the camera’s death, even when given over two decades to supersede it.

In addition, the self-sufficiency of current applications ensures that artists do not need to fear robotic plagiarism. According to DALL-E’s lead researcher Mark Chen, these technologies view millions of images and recognize patterns within their data to form their own artistic language, allowing them to create independently. While works on the internet benefit AI by serving as data, Chen said leaders in the field propose solutions that will keep idea theft at bay.

“‘We continue to work with artists and have them provide feedback,'” Chen said. “‘There’s a lot of solutions that are being floated around in this space, like potentially disabling the ability to generate in a particular style. But there’s also this element of inspiration that you get, like people learn from imitation of masters.’”

For artists, the future seems bleak. They may wonder why anyone would buy their pieces if AI becomes faster, smarter and, ultimately, better. Author Krzysztof J. Pelc pointed out in his book “Beyond Self-Interest: Why the Market Rewards Those Who Reject It” the indirect relationship between one’s success in the market and their investment in it, invalidating the utility of artists’ fear.

“We find individual passion reassuring,” Pelc said. “Artists face an extreme version of this whim; their market success depends on being seen as oblivious to market success.”

The infamous trope of man vs. machine is just that — a trope. To seek victory against AI necessitates an attachment to the past. Humanity must accept AI in the artistic sphere, not just its presence but its intricacies. With this change in opinion will come the true victory: the privilege to question, wonder and create without worry.

![Freshman Milan Earl and sophomore Lucy Kaplan sit with their grandparents at Archer’s annual Grandparents and Special Friends Day Friday, March 15. The event took place over three 75-minute sessions. “[I hope my grandparents] gain an understanding about what I do, Kaplan said, because I know they ask a lot of questions and can sort of see what I do in school and what the experience is like to be here.](https://archeroracle.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/grandparents-day-option-2-1200x800.jpg)