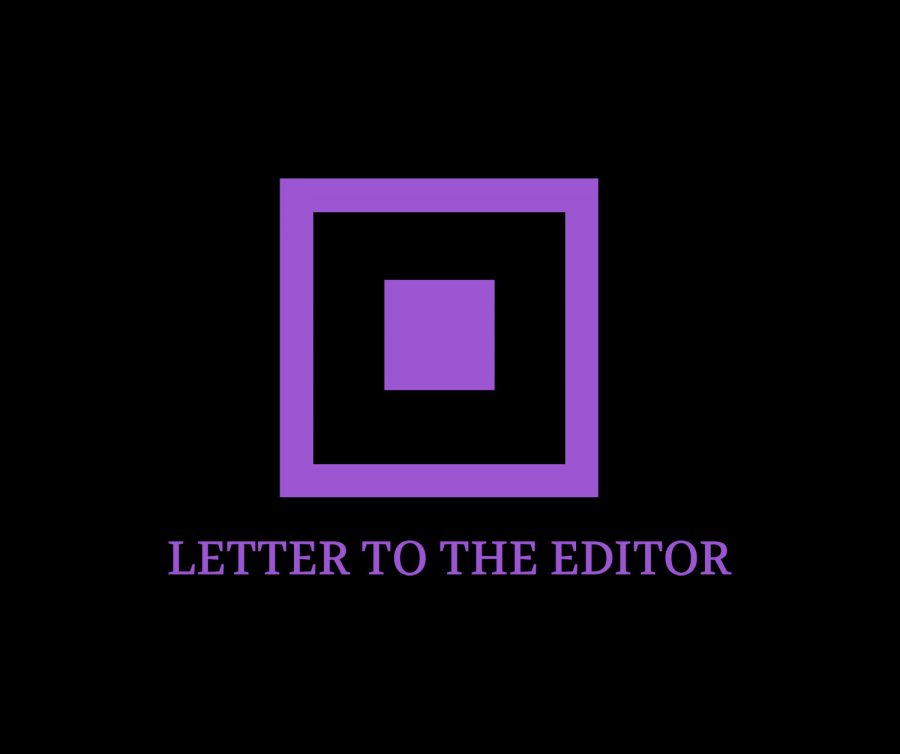

Op-Ed: I’m not a guest, I’m a member

Photo credit: Lola Thomas

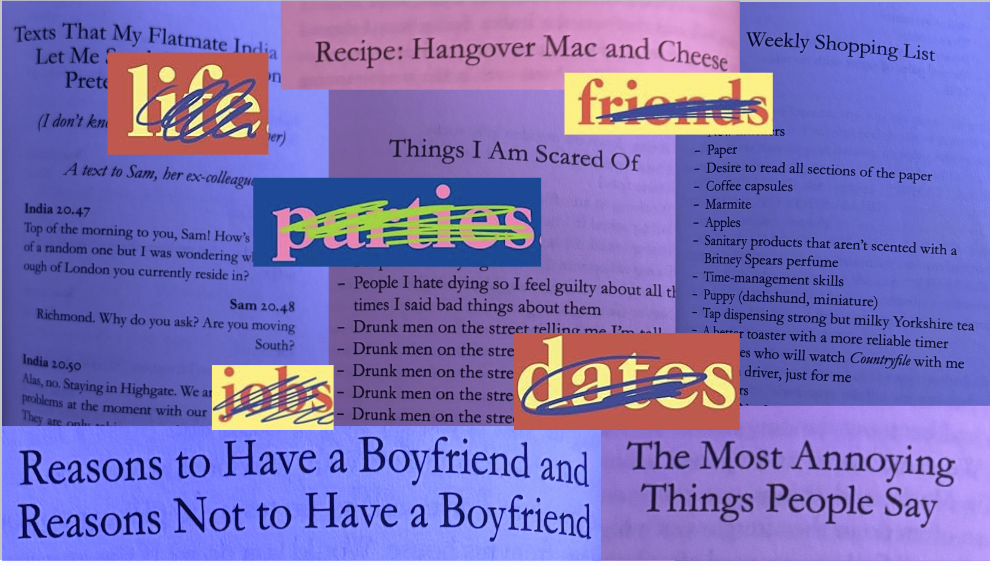

This illustration shows a Black girl with an afro. Since second grade, I’ve attended predominately white schools and have often been discriminated against for my natural hair. (Graphic Illustration by Lola Thomas)

May 21, 2023

“Is your hair fake?”

“You speak so well; I’m shocked!”

“You got in because you’re Black.”

“You’re so pretty, for a Black girl.”

“Don’t steal anything; I’m watching you.”

I have heard these comments from students and teachers since I was at least 10 years old. From second to sixth grade, I attended a predominantly white elementary school in Bel Air. The school gave me a wealth of opportunities and experiences I will cherish. I learned about the intricate anatomy of squids, acted out the revolutionary war in a school production of “Hamilton” and constructed a literary foundation of Marcel Proust, Gabriel Garcia Marquez and Nancy Drew novels.

However, one thing the school didn’t seem to get right was fostering a safe and comfortable environment for me as a Black girl.

I distinctly remember roaming around my first Scholastic Book Fair at school with at least 17 books up to my nose. It was a mirage of knowledge and stories I wanted to immerse myself in immediately. I was also intrigued by the pastel gel markers and sequin bookmarks.

As my beaded braids clicked and clacked with every excited step toward the glitter pens and pom-pom notebooks, I was stopped by the school librarian. She warned me not to steal anything, and she said she was keeping an eye on me. At that moment, she must have been 8 feet tall.

Growing up, I never saw my race as something to be ashamed of. I was aware of it, but to me, it was a gift. I was proud of how my afro bounced and picked up the sunlight, and when I was little, I would call it my crown. I was proud of my Guyanese and Creole heritage and the smell of curry and gumbo wafting throughout my house. But at that school, my afro was a fruitless crown, one tarnished and meant to be made fun of — not to mention my eccentric food looked and smelled too different to be accepted. I will never let my experience going to a predominantly white school erase my pride, but I will admit it has shaped me.

When being discriminated against, the experience is harder to deal with when there is a lack of help given by the administration. The most common response I get is, “Kids will be kids, they don’t know what they’re saying is offensive,” and in high school social groups, it’s simply, “Get over it.” These responses invalidate Black experiences.

If schools better handle cases of discrimination, students of color will feel safer and more accepted in their communities. Little to no action against racism makes school a more hostile and isolating place.

Implementing Black history and experiences in the curriculum can also help Black students feel more accepted. At my old school, we rarely learned anything about Black culture, and if we did, we never learned about the beauty or diversity of it. Black History Month was never celebrated until a couple of other Black students and I started daily presentations at assemblies. It felt like the administration made no effort to make students of color feel accepted.

It’s important for predominantly white schools to put in the effort to make Black students feel like they’re in an accepting community. We deserve to go through the day without teachers calling us other Black students’ names. We are each our own individual person; I’m not an honorary token guest at your school, I’m a member. Treat me like one.